For examples of well worded objectives, see Appendix E - Characteristics of Good Objectives.

Figure 10. Improvement with spring and fall (cool season) use occurred on Susie Creek, Nevada, which was grazed until 1991 with annual hot-season use by cow-calf pairs.

Figure 10. Improvement with spring and fall (cool season) use occurred on Susie Creek, Nevada, which was grazed until 1991 with annual hot-season use by cow-calf pairs.

By 1999, spring and fall (cool-season) grazing by cow-calf pairs allowed willow recovery.

By 1999, spring and fall (cool-season) grazing by cow-calf pairs allowed willow recovery.

By 2007, beaver occupied the reach,

By 2007, beaver occupied the reach,

and by 2012 recovery is transitioning the area to cattails,

and by 2012 recovery is transitioning the area to cattails,

and by 2014, a meadow.

and by 2014, a meadow.

Resilience in 2017 was based on riparian functions and plant species that grow up through deposited sediment.

Resilience in 2017 was based on riparian functions and plant species that grow up through deposited sediment.

While the changes here were not all predicted, Objectives about riparian stabilizers would have focused management for return of riparian functions.

While the changes here were not all predicted, Objectives about riparian stabilizers would have focused management for return of riparian functions.

The scale for objectives should match the scale and focus of the planned management and the timeline for making management decisions. Some objectives should reflect landscape-scale questions such as: Are pinyon and/or juniper trees encroaching? Is distribution of invasive weeds expanding? Is the landscape becoming more homogeneous? Other objectives should focus on important critical areas or key areas such as important species on a large or important ecological site (See Appendix F - Scales in Monitoring). All objectives should track from the issues through the planned management and into the use of monitoring information for adaptive management.

Since the success or failure of adaptive management is determined by tracking changes in resources over time, objectives must be measurable attributes of the resources that are directly affected by the management actions. For example, for livestock grazing management, plant species composition or community structure is appropriate to describe a desired plant community within the potential of a specific ecological site. These resource characteristics respond directly to livestock use and are sensitive to changes in grazing management. Likewise, riparian characteristics, such as willows and amount of streambanks dominated by stabilizing species on a specific stream reach, are resource attributes that can be directly affected by livestock use and respond to management changes in many settings. It is paramount that the selected resource objectives be site-specific, within the site and state's capabilities, and clearly predicted from planned livestock grazing or other management. After crossing an ecological or geomorphic threshold, it is not reasonable to base an objective on the previous state without significant investment (and often risk) associated with active restoration; that is, not just a change in management.

Objectives should be quantitative statements of desired future conditions based upon the capabilities and limitations of the ecological site. Desired future conditions could include such resource attributes as vegetation, soil and water quality. Desired plant community phase is a quantitative expression of the plant community that exists or may exist on a specific site and that management actions are designed to maintain or produce. The desired plant community phase must be within the site's current state unless active restoration is applied.

Usually the desired plant community phase will be achieved and maintained through reasonably applied management actions. In places (almost everywhere) where vegetation is expected to continue to change through time or cycle because of disturbances, such as periodic fire (or vegetation management that replaces the role of fire) followed by plant succession, the desired plant community phase is dynamic. It can be expressed as an approximate proportion of the landscape in various stages of the cycle and/or expressed as a range of conditions that ensures resilience after disturbance. State and transition model concepts can be used to ensure that vegetation represent sustainable resilience of ecological processes; that is, plant communities that resist transition across ecological thresholds. Expressly describing disturbance regimes helps to convey the dynamic nature of rangeland vegetation at an appropriate spatial and temporal scale. Desired future condition is analogous to desired future plant community phase, but has a broader perspective including other measurable resource attributes or features in addition to the vegetation resource (e.g., channel width, width/depth ratio, soil quality, etc.).

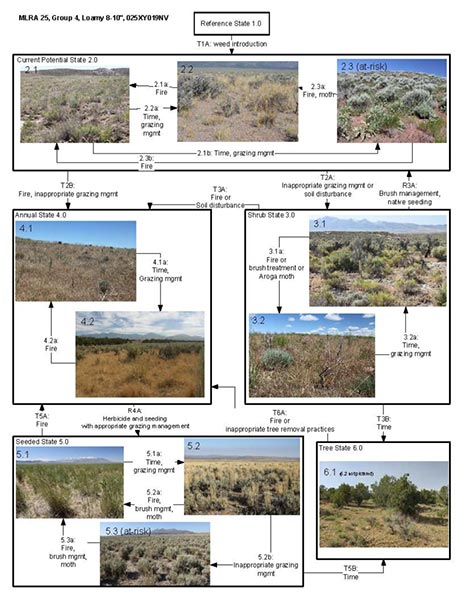

Figure 11. A STM describes alternative states (black boxes), processes and mechanisms (e.g. 2.1a) that cause plant community changes (pathways) to phases within states (photos), maintenance of a current state (e.g. 2.3b), transitions between states (e.g.T2A), and restoration toward a previous state (e.g. R3A). See Appendix B - Ecological Sites.

Figure 11. A STM describes alternative states (black boxes), processes and mechanisms (e.g. 2.1a) that cause plant community changes (pathways) to phases within states (photos), maintenance of a current state (e.g. 2.3b), transitions between states (e.g.T2A), and restoration toward a previous state (e.g. R3A). See Appendix B - Ecological Sites.