Each AIM-monitoring survey uses standardized field methods and a set of core indicators (amount of bare ground, vegetation composition, nonnative invasive plant species, plant species of management concern, vegetation height, and proportion of soil surface in large inter-canopy gaps), remote sensing, and a statistically valid study design to track changes at broad scales (MacKinnon et al. 2011). The core indicators and standard methods should also be used at the site-scale of management when they address the site specific objectives. If not, alternate methods should be used as needed.

Remote sensing informs connections among scales. It provided an essential platform for mapping soils and ecological sites (Caudle et al. 2013); documented the large-scale issue with loss of sagebrush habitats (LANDFIRE 2013); was intended for extrapolation of AIM ground-based data (Toevs et al. 2011); and helped identify and map sage-grouse seasonal habitats, habitat quality, and limiting factors (Coates et al. 2014; Nevada Sagebrush Ecosystem Technical Team 2014). It remains extremely useful in locating representative key areas for long-term monitoring and extrapolating ground-truthed data to larger landscape units (Appendix G — Remote Sensing to Monitor Rangelands).

Other Scale Tools and Considerations

State-and-transition-model-based ecological site descriptions provide the basis for all levels of rangeland management (Caudle et al. 2013). They facilitate awareness about risky transitional pathways, as well as restoration or other pathways among states or phases. Disturbance response groups (DRG) help to link similar threats and ecological thresholds across landscapes by grouping similarly behaving ecological sites (Stringham et al. 2016). This enables strategic landscape-scale planning addressing parts of a mapped unit of a DRG in a similar state and phase contrasted with other areas in a different state or phase, or contrasted with different ecological sites in a different DRG.

The Nevada Greater Sage-Grouse Conservation Plan calls for monitoring at two scales: 1) “inventory monitoring” at a broad scale, and 2) monitoring for tracking and adapting site-specific management. The plan calls for integration of federal data such as discussed above, with Nevada data (including data from private land). State data includes fire numbers and sizes, sage-grouse population trends, extent of weeds and invasive species, weather (growing conditions etc.), functional acres lost or gained as tracked for the “Conservation Credit System,” and other data (Sagebrush Ecosystem Council and Technical Team 2014).

Successful monitoring occurs at various scales, and the focus of most managers is at the scale of their management responsibilities or of the plans and decisions they write, implement and adapt. National data sets, such as AIM, and identified issues may influence goal setting, selection of treatments, and selection of key areas needed for adaptive management of local land uses or treatments. The national data sets rarely contain data from locations chosen with the criteria for key areas described in Appendix H – Procedures for Selecting Key areas and Key Species.

For sage-grouse issues, environmental impact statement objectives table 2-2 (BLM) and 1A and 1B (FS) inform managers about the general characteristics of habitats desired by sage-grouse. AIM, remote sensing or other broad-scale data may suggest that for a population, a particular seasonal habitat is likely limiting. Then managers use transitional pathways in ecological site descriptions to consider opportunities and threats in a particular management unit, and select one or more key area(s) to monitor the site-scale (Stiver et al. 2015)) long-term effects of implemented management strategies. Range managers have been doing something similar for decades using a general understanding of what is important for rangeland management in a given management unit. They select key areas for measuring achievement of objectives driving planned management, document actions with short-term monitoring and test ideas with long-term monitoring.

Long-term monitoring at that key area could use methods identical to, similar to or different from data collection methods in AIM, depending on the question. Methods selected would depend on site specific objectives and the data needed to determine if management in that area was meeting those objectives. If AIM methods were used, the data from the key area would usually not be analyzed with other AIM plot data, because the key area location was not randomly located at the right scale. For statistical reliability, plots for AIM data are randomly located across the district, state and nation, with livestock management units having no bearing on the stratification. Plots should not be intentionally placed on an existing or new key area because that would not be a random location representing the district, state or nation. AIM data that happen to be from a plot in a pasture are not likely to be reliable for adaptive management of grazing in that pasture because the plot was not likely to be from a place sensitive to management or that reflects objectives (see Appendix H – Procedures for Selecting Key Areas and Key Species). Instead of using a key area for monitoring, many random plots could be used to achieve statistical reliability (Appendix I – Statistical Considerations) within a pasture. However, that approach is not feasible for grazing management on a limited budget.

The precise location of a key area plot can be random within a representative landscape component. For example, a key area can represent an appropriate ecological site in an appropriate state and phase and at an appropriate distance from water or receiving representative levels of use, etc. (Appendix H – Procedures for Selecting Key areas and Key Species).

In land use plans (BLM resource management plans or FS land and resource management plans), objectives or desired future conditions may be stated, as they are for sage-grouse in Habitat Objectives tables 2-2 (BLM) and 1a and 1b (FS) in the greater sage-grouse Record of Decision and Land -use Plan Amendments (BLM 2015 and FS 2015). The habitat assessment framework (HAF) (Stiver et al. 2015) contains similarly general criteria for suitable, marginal and unsuitable habitat quality. Such criteria or objective tables are statements analogous to long-term objectives, but they are general in nature and don’t adequately consider ecological site descriptions until locally applied. Stringham and Snyder (2017) determined that many of these criteria cannot or should not be achieved on many ecological sites, especially Wyoming big and low sagebrush sites, at least within Major Land Resource Area 25. In using them for site-scale monitoring, the preponderance of the evidence should guide SMART objectives tailored for local ecological sites and a carefully chosen key area. Each individual table attribute cannot be used as a make-or-break criterion. Criteria or table attributes should inform strategic management targeting areas and changes in conditions where there are important opportunities for improvement. Without a restoration pathway to another state, the current state is the potential. With a restoration pathway, the higher state is the potential. Pathways for accomplishing vegetation (state or phase) changes vary widely in their expense and likelihood for success.

Permit renewal, and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) analysis that supports it, relies on data from many scales and sources. All of the data described here and additional information about past management and its effects from permittees and agency files (Appendix A - Cooperative Monitoring) informs the conversation about: 1) resource concerns; 2) SMART objectives; 3) management tools and strategies; 4) short-term monitoring tied to the chosen tools strategies and objectives; 5) long-term monitoring at specific key areas using appropriate methods; 6) analysis of monitoring information and possibly extrapolation of key area data using remote sensing; and 7) flexibility, responsibility and adaptive management.

There has been a great deal of discussion about the plant height and sagebrush cover objectives in tables 2-2 and 1a & 1b. With these or any new version of a table addressing habitat objectives considered as long-term objectives, or used to inform setting objectives, managers can apply a diverse set of targeted strategies in sites with the potential (site and state) to support taller plants or not (Stringham and Snyder 2017). Sampling plant height across space and time allows managers to use concentration of livestock with an annual rotation as a tool to provide shorter grazing periods with less stress to favored plants, as well as more recovery time to facilitate regrowth and success of taller grasses. This may be more strategic than attempting to limit utilization, which often leads to uneven distribution or more fire risk from fine fuels.

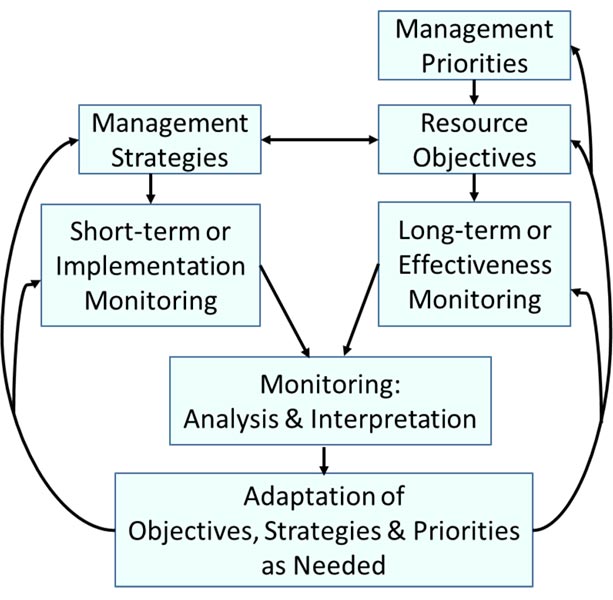

Adaptive management should not be used to restrict available responses, but instead should be used to encourage flexibility by considering a variety of responses. It is the use of monitoring to track implementation of management strategies and results, and to select different strategies (response) if implementation is not feasible or effective (threshold) for accomplishing objectives. It is critically important to connect short-term monitoring to the strategies chosen for effective management to attain long-term objectives. There are many tools in the management toolbox. Adaptive management can also occur within a planning/permitting cycle, such as by using the grazing response index (GRI) or a similar index of management effect to adjust season (dates of use and growing season nonuse) and intensity of use next year based on the record of season, duration and intensity of use this year.

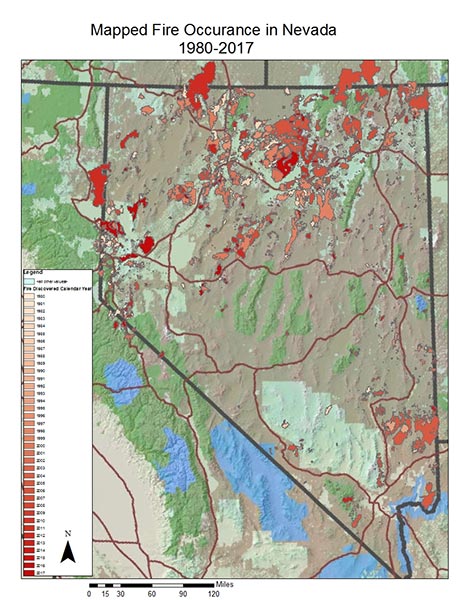

Figure 49. In recent decades, fires in Nevada have become larger and more frequent. This has changed many sagebrush habitats.

Figure 49. In recent decades, fires in Nevada have become larger and more frequent. This has changed many sagebrush habitats.

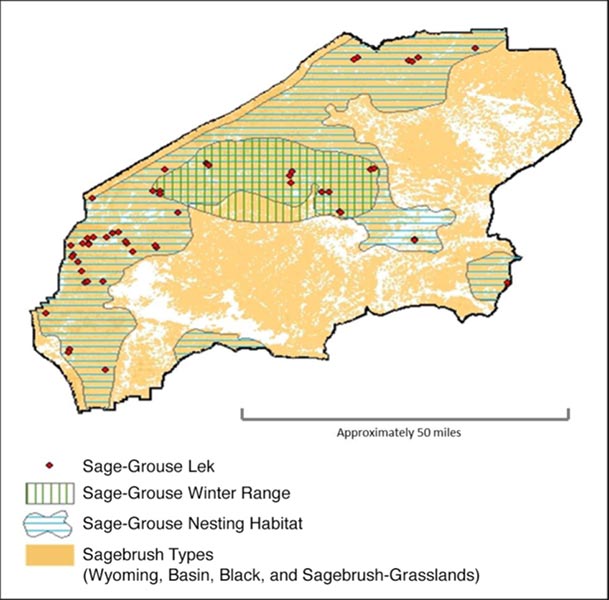

Figure 50. Sage-grouse management planning occurs at various scales.

Figure 50. Sage-grouse management planning occurs at various scales.

Figure 51. Measuring progress toward objectives in carefully selected key areas enables data to be used strategically for adapting management.

Figure 51. Measuring progress toward objectives in carefully selected key areas enables data to be used strategically for adapting management.

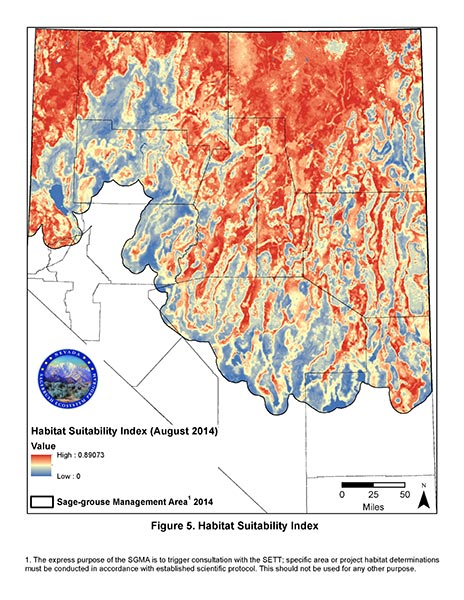

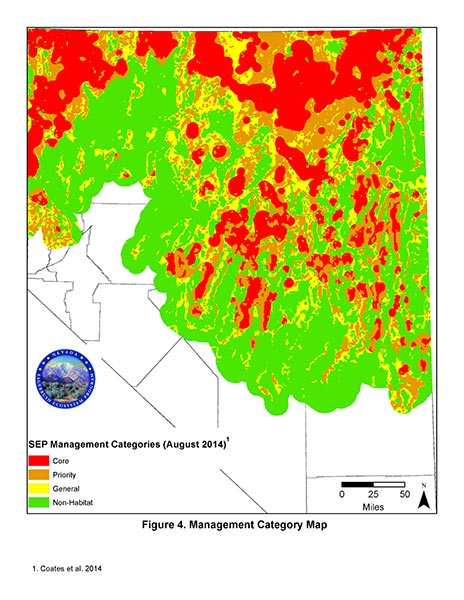

Figure 52. Habitat suitability mapping based on sage-grouse habitat use studies and remote sensing have been used

Figure 52. Habitat suitability mapping based on sage-grouse habitat use studies and remote sensing have been used

to create the management category map that helps managers focus on priority areas (Coates et al 2014).

to create the management category map that helps managers focus on priority areas (Coates et al 2014).

Figure 53. Adaptive management requires using long-term monitoring to evaluate progress toward objectives and short-term monitoring to understand what management has been implemented.

Figure 53. Adaptive management requires using long-term monitoring to evaluate progress toward objectives and short-term monitoring to understand what management has been implemented.