This is the sixth fact sheet in a series describing a research study of water right owners in the Walker River Basin. The previous fact sheets described: 1) the objectives and methodology of the study; (FS-04-49) 2) farming and ranching operations and demographic characteristics of respondents (FS-04-60); 3) attitudes toward Walker Lake (FS-05-37); 4) attitudes of water right owners concerning their willingness to sell or lease decree water rights (FS-05-54); and 5) attitudes of selected Walker River Basin water right owners concerning their willingness to sell or lease storage water rights (FS-05-55). This sixth and final fact sheet compares the perceptions and attitudes of selected Walker River Basin water right owners on environmental priorities within the basin.

Introduction

The Walker River Basin, running from the eastern slopes of the Sierras in California to a desert lake in Nevada, has been the source of major controversy for farmers, ranchers, environmentalists, Indian Tribes and federal/state agencies for decades. The Walker River faces the same fate of other rivers just like it in the West. The demand for water is never-ending, and conflict arises based on the allocation of water and its right of use. The challenge for those involved is to understand the lifestyle, custom and culture of every community, individual and species affected by water use in the Walker River Basin.

A six-page, 38 item, questionnaire was developed in cooperation with the Mono County, Smith Valley and Mason Valley Conservation Districts. Due to the small geographic survey area, high agriculture use areas were randomly targeted within the Walker River Basin using "Area Frames" (Salant and Dillman, 1994). Collection of survey data began on June 28, 2003 with the Walker River Indian Reservation and was completed on September 7, 2003 in the Smith Valley area. Due to the unavailability of agriculture use data and time constraints, the Bridgeport area was not randomly surveyed. There were 139 individuals contacted out the possible 520 using the variable of selected high agriculture use areas described above. Twentythree individuals declined to participate in the study and 116 individuals completed the survey. (Emm, 2003).

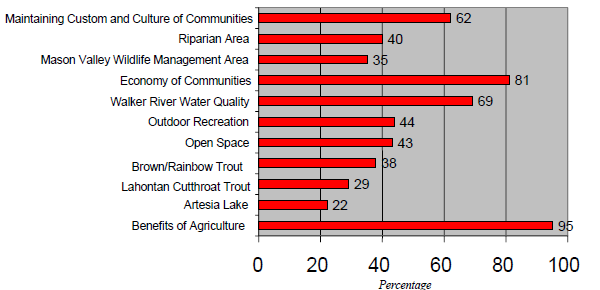

Graph 1: Walker River Basin Research Study: Percentage of Group Priorities that were Most Important

| Group Priority |

Percentage |

| Maintaining Custom and Culture of Communities |

62% |

| Riparian Area |

40% |

| Mason Valley Wildlife Management Area |

35% |

| Economy of Communities |

81% |

| Walker River Water Quality |

69% |

| Outdoor Recreation |

44% |

| Open Space |

43% |

| Brown/Rainbow Trout |

38% |

| Lahontan Cutthroat Trout |

29% |

| Artesia Lake |

22% |

| Benefits of Agriculture |

95% |

Environmental Priorities

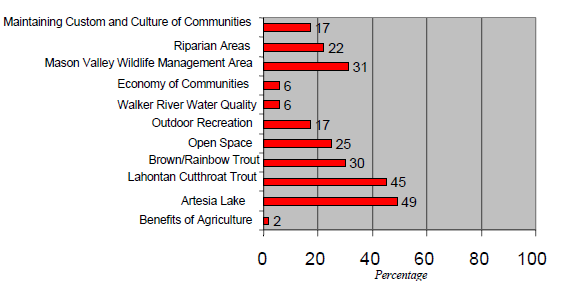

One of the objectives of this research study was to compare the environmental priorities within the basin to the perceptions and attitudes of selected Walker River Basin water right owners. The survey questionnaire identified 11 different priorities and asked respondents if they were important or unimportant. The 11 identified priorities included (1)benefits of agriculture production; (2) Artesia Lake; (3) Lahontan Cutthroat Trout fishery; (4) Brown Trout/Rainbow Trout fishery; (5) open space (in terms of development); (6) outdoor recreation; (7) Walker River water quality; (8) economy of area communities; (9) Mason Valley wildlife management area; (10) riparian areas; and (11) maintaining custom and culture of area communities. Graph 1 show the percentages concerning the topics that were rated the most important or highest rated priorities. Benefits of agriculture were the highest rated priority at 95% followed by the economy of area communities at 81%. Graph 2 shows the percentages for the topics that were rated the least important or lowest rated priorities. Forty-nine percent of the respondents reported that Artesia Lake was not important while 45% said Lahontan Cutthroat Trout and 30% said Brown/Rainbow Trout fisheries were not important.

Graph 2: Walker River Basin Research Study: Percentage of Group Priorities that were Not Important

| Group Priority |

Percentage |

| Maintaining Custom and Culture of Communities |

17% |

| Riparian Area |

22% |

| Mason Valley Wildlife Management Area |

31% |

| Economy of Communities |

6% |

| Walker River Water Quality |

6% |

| Outdoor Recreation |

17% |

| Open Space |

25% |

| Brown/Rainbow Trout |

30% |

| Lahontan Cutthroat Trout |

45% |

| Artesia Lake |

49% |

| Benefits of Agriculture |

2% |

Fisheries

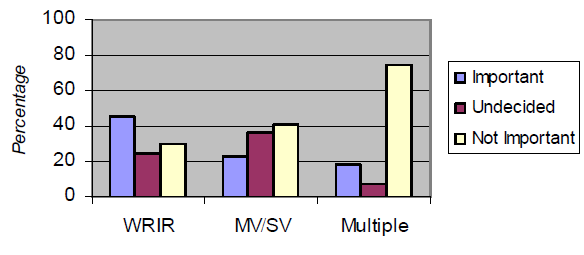

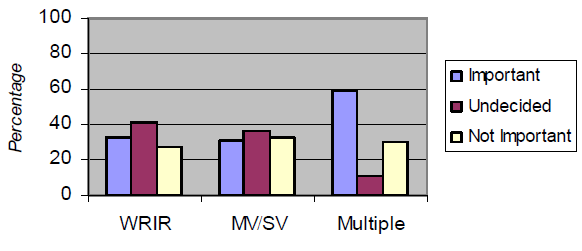

There were two items in the survey questionnaire that listed the Lahontan Cutthroat Trout and the Rainbow Trout/Brown Trout fisheries. Respondents were asked to rate the importance of these fisheries. Findings indicate there were differences among responses from the three different geographical areas, the Walker River Indian Reservation (WRIR), Mason Valley/Smith Valley (MV/SV), and Multiple that represented Antelope Valley, Bridgeport Valley and those that own water rights in more than one area of the basin. Overall, 45.1% of the respondents felt that the Lahontan Cutthroat Trout were unimportant while 29.2% felt they were important and 25.7 percent were undecided. Refer to Graph 3 for a percentage breakdown by area. Additionally, 30.1% of respondents felt the Brown Trout/Rainbow Trout fisheries were unimportant, while 38.1% felt it was important, and 31.9% were undecided. Graph 4 illustrates a percentage breakdown by area.

Graph 3: Walker River Basin Research Study: Importance of Lahontan Cutthroat Trout

| Group Priority |

Important Percentage |

Undecided Percentage |

Not Important Percentage |

| WRIR |

~43% |

~23% |

~28 |

| MV/SV |

~22% |

~38% |

~41% |

| Multiple |

~19% |

~7% |

~78% |

| The Walker River Indian Reservation is WRIR. Mason Valley and Smith Valley is MV/SV. Multiple represents Antelope Valley, Bridgeport Valley and those that own water rights in more than one area of the basin. |

Graph 4: Walker River Basin Research Study: Importance of Brown Trout/Rainbow Trout

| Group Priority |

Important Percentage |

Undecided Percentage |

Not Important Percentage |

| WRIR |

~35% |

~41% |

~26% |

| MV/SV |

~34% |

~38% |

~36% |

| Multiple |

~60% |

~10% |

~30% |

Conclusions

This research study was conducted to identify commonalities and differences that existed between those individuals that actually own the right of use of water in the Walker River Basin in an effort to better understand viewpoints of this group of people. This report describes one group of water users. This research study is not intended to favor one side or another, but rather seek to measure attitudes and opinions of the groups that use Walker River water. The respondents in this research study rated 11 identified environmental priorities. The benefits of agriculture and the economy of area communities were the most important environmental priorities in this study followed closely by Walker River water quality.

Respondents also identified the least important environmental priorities. Respondents reported that Artesia Lake, fisheries and Mason Valley Wildlife Management Area were the least important priorities. However, it must be noted that the “not important” category was selected by less than 50% of respondents. This means that more than half of the respondents were either undecided or felt it was an important priority.

There were differences found between the geographical areas concerning perceptions and attitudes involving fisheries. This may be a reflection of the fisheries that are located in each area. For example, Lahontan Cutthroat Trout are found at the lower end of the basin in Walker Lake and the lower part of the Walker River. The Brown /Rainbow Trout fisheries are in the headwaters (Multiple) area of the system and in the upper reaches of the Walker River. Despite these geographical differences, some respondents were still undecided as to whether or not fisheries were an important environmental priority.

This research information may be used as one of several sources in trying to reach potential solutions for complex environmental questions regarding the Walker River Basin. This study identifies the differences and commonalities among the respondents concerning environmental priorities. The authors hope that the information will be useful for those seeking to resolve environmental conflicts through the consideration of different view points. It has been shown that decisions made through a collaborative process are more likely to be implemented (Singletary, Ball, Rebori, UNCE SP-00-04) One step in the collaborative process is to understand the views and values of others in an effort to find common ground. This data is provided for that purpose as discussions continue regarding use of water in the Walker River Basin.

References

California Department of Water Resources. 1992. Walker River Atlas. Sacramento, CA. State of California, Department of Water Resources.

Emm, S. 2003. Perceptions and Attitudes of Randomly Chosen Agriculture Water Right Owners in Selected Areas of the Walker River Basin Toward Walker Lake. M.A. Thesis, Colorado State University.

Salant, P. and Dillman, D.A., 1994. How to Conduct Your Own Survey. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. New York.

Singletary. 2005. Collaborative Approaches and Communication Skills for Addressing Water Disputes. UNR. University of Nevada Fact Sheet 05-24.

Singletary, L., A. Ball, and M. Rebori. 2000. Managing Natural Resource Disputes. University of Nevada Cooperative Extension. SP-00-04.

Emm, S., Breazeale, D., and Smith, M.

2007,

Walker River Basin Research Study: Environmental Priorities,

Extension | University of Nevada, Reno, FS-07-02