Introduction

Walker Lake is a rare perennial desert terminal lake located in Mineral County, Nevada. The unique terrain around Walker Lake is mostly mountainous with canyons and large arid plateaus. Walker Lake is the end of the line for Walker River Basin river flow.

Walker Lake is one of the last remaining remnants of Ancient Lake Lahontan existing 75,000 to 10,000 years ago in the Great Basin. Lake Lahontan, at its peak surface elevation, extended just below the Nevada- Oregon border in the north to just south of present-day Hawthorne. (Nevada Department of Water Resources, 2008) The two well-known remaining remnants of Lake Lahontan in Nevada are Walker Lake and Pyramid Lake.

This fact sheet is written as a tool for the public to find additional information about Walker Lake and understand how water flows in the Walker River Basin. Websites are listed that can provide the reader with additional specific information. The topics in this fact sheet are related to questions asked by Mineral County residents over the last three years.

Photo by Betty Easley

Walker River Basin

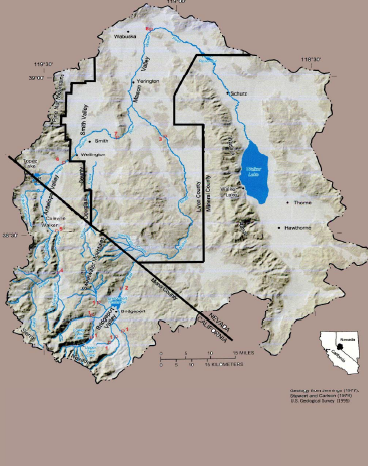

Walker Lake is the terminus point of the Walker River Basin. The Walker River Basin encompasses approximately 4,050 sq. miles (2,591,900 acres) and is the primary source of surface water into Walker Lake. The river travels generally in a northeasterly direction from the headwaters in the higher elevations of the Sierra Nevada mountains in the southwest to the eastern edge of Mineral County and Walker Lake (Nevada Department of Water Resources, 2008). The basin includes Mono County, California, the Walker River Paiute Indian Reservation and several counties in Nevada, including Mineral, Douglas and Lyon counties.

Water Flow and Monitoring

The Walker River begins at its headwaters in California where the East Walker River and the West Walker River begin. The confluence of these two forks in Nevada is located about seven river miles upstream from Yerington and continues to flow through Weber Reservoir and into Walker Lake. Refer to Figure 1 for a graphic view of water flow.

The Walker River, like most rivers in the West, is fed by other small rivers because of melting snow. The surface water or stream flow of the Walker River is measured at different points on the river by the U.S. Geological Survey. The red numbers on Figure 1 represent some of the measuring sites monitored. Specific water flow data is available to the public at the following website: USGS.

Photo by Betty Easley

Water Quality

The surface area of Walker Lake is declining, which results in a degradation of water quality and increased salt content known as Total Dissolved Solids (TDS). TDS is added to Walker Lake from the following sources: Walker River in-stream flows, groundwater inflow, salts carried by the wind and salts moving upward into the lake from lake-bottom sediments. Walker Lake TDS levels change primarily based on the amount of water in the lake (U.S. Geological Survey, 1995).

The concentration of TDS fluctuates in response to the amount of water entering the lake and evaporating from the lake. The TDS was 2,500 milligrams per liter (mg/L) in 1882 and was 13,300 mg/L in July of 1994 (U.S. Geological Survey, 1995). The State of Nevada has a “Surface Water Monitoring Network” and currently takes water samples from Walker Lake to test water quality. Test results from March 3, 2007, show TDS levels of 15,060 mg/L at the Walker Lake 2 South- Epilimnion testing site and TDS levels of 15,010 mg/L at the Walker Lake 3 Center Epilimnion test site (NDWR, 2008). Specific Walker Lake water quality data are available to the public at the following website: NDEP.

The increase in the amount of total dissolved solids threatens the Walker Lake ecosystem and fish and birds that depend on the ecosystem. The Lahontan Cutthroat Trout (LCT) is the only species of trout found in Walker Lake. The LCT was listed as threatened in 1975 (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2008). LCT populations’ potential for survival is impacted by increased TDS levels. The Nevada Department of Wildlife, the Walker River Paiute Tribe and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service are monitoring the LCT fishery at Walker Lake.

Figure 1: Walker River Basin water flow is in blue. Numbers in red represent streamflow measurement stations

Printed with permission of the U.S. Geological Survey

Water Rights

Walker Lake is a natural resource at the terminus of the Walker River Basin that is not allocated water rights under Federal Court Decree C-125. However, there are efforts for the acquisition of water rights for Walker Lake under the Walker River Basin Project directed by Nevada System of Higher Education. The website for the Walker River Basin Project is located at NSHE.

Decree C-125 is based on prior appropriation doctrine. The premise of prior appropriation is seniority: “first in time, first in right.” Under prior appropriation, the first user is guaranteed supply based on the supply in the system. The next senior right has the second priority and so on down the line as long as there is water flowing in the river. There can only be utilitarian extractive uses eligible for the water in the system such as mining, farming, ranching, municipal, industrial and domestic.

A water user, under prior appropriation, automatically acquires a vested property right protected by the Constitution at the point and time the water was diverted from the river. (Wilkenson, 1997)

Summary

Walker Lake is one of the last remaining remnants of Ancient Lake Lahontan existing 75,000 to 10,000 years ago in the Great Basin. Located in Mineral County, Walker Lake depends primarily on Walker River stream flows and is a major natural resource priority to Mineral County residents (Emm, 2004).

The Walker River begins in the headwaters in California where the East Walker River and the West Walker River begin to flow. The confluence of these two forks is located about seven river miles upstream from the Yerington, located in Lyon County and Mason Valley. The merged West Walker River and East Walker River, the main stem of the Walker River, continue to flow in a northerly direction through the Wabuska gauge and Weber reservoir to Walker Lake.

The concentration of TDS fluctuates in response to the amount of water entering the lake and evaporating from the lake. The increase in the amount of TDS is threatening the Walker Lake ecosystem and the fish and birds that depend on the ecosystem. The increased TDS in Walker Lake have impacted LCT survival rates.

Walker Lake currently does not have water rights in Decree C-125; however, there are efforts under the Walker River Basin Project for the acquisition of water rights and a lawsuit pending through efforts of the Walker Lake Working Group and Mineral County.

References

Emm, S. (2003). Perceptions and Attitudes of Randomly Chosen Agriculture Water Right Owners in Selected Areas of the Walker River Basin Toward Walker Lake. Thesis, Colorado State University.

Emm, S. (2004). Mineral County Needs Assessment Community Needs and Issues. University of Nevada Cooperative Extension. FS-04-50.

Nevada Department of Water Resources. (2008) Walker Lake Nutrients/Metals Data. Nevada Department of Environmental Protection. Retrieved on 1/23/08. Retrieved from NDEP.

Nevada Department of Water Resources. (2008). Walker River Chronology Part I. Nevada Department of Environmental Protection. Retrieved on 1/20/08. Retrieved from Water NV

Wilkinson, C. (1997). Paradise Revised. Center of the American West. Atlas of the New West. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (2008) Lahontan Cutthroat Trout. United States Department of Interior. Retrieved on 1/22/08. Retrieved from FWS.

U.S. Geological Survey. Water Budget and Salinity of Walker Lake, Western Nevada. (1995). United States Department of Interior. Fact Sheet FS-115-95.

Emm, S. and Zuniga, K.

2008,

Walker Lake: A Snapshot of Water Flow and Water Quality,

Extension | University of Nevada, Reno, FS-08-08