Introduction

If a desert is a place where water is hard to find, a food desert is an area where healthy food is hard to come by. Having healthy foods in one’s immediate neighborhood from places such as stores, farmers markets or community gardens influences one’s food choices and what one eats. Selection of these healthful foods can reduce ones risk of obesity and diet-related diseases, diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Smith & Miller, 2011).

Supermarkets and grocery stores can offer a variety of affordable and healthy foods such as: fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and dairy. Without supermarkets close to home, residents depend more on convenience stores and fastfood restaurants for their food sources (Spence, Cutumisu, Edwards, Raine, & Smoyer-Tomie, 2009). Areas with poor access to large food outlets are known as “food deserts”.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines a food desert when a census tract meets the following two criteria (USDA, 2014a):

- Low-income community - poverty rate of 20 percent or higher, or a median family income at or below 80 percent of the statewide median family income

- Low-access community - urban census tracts with more than 33 percent living more than one mile from a supermarket or large grocery store or rural census tracts (geographical region containing 1,000 to 8,000 people) that are more than 10 miles from a supermarket or large grocery store.

The 2010 Census food desert analysis deviated from the established USDA definition stated above. A low-income community requires 40 percent of the population to have an income at or below 200 percent of federal poverty thresholds for family size (Ver Ploeg et al., 2012). Of interest, using the alternate low-income classification, 29.7 million people live in low income census tracts more than 1 mile from a supermarket.

Specifically, 9.9 million individuals residing in urban areas or 18 percent live in a food desert (low-income areas more than 1 mile from a supermarket) and 18.3 million individuals or 10 percent residing in rural areas live in a food desert (low-income areas more than 10 miles from a supermarket) (Ver Ploeg et al., 2012).

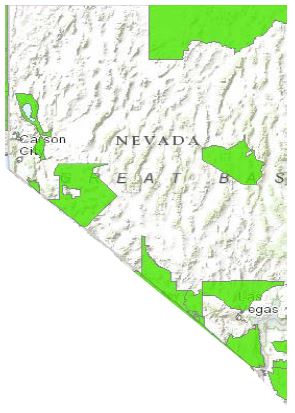

The government has mapped food deserts in the United States, identifying communities that have limited access to healthy food choices (USDA, 2014b). Data specific to Nevada is presented below.

Nevada State

- USDA identified food deserts in 40 of 687 census tracts in Nevada.

- 154,623 Nevadans meet the criteria of living in a low-income food desert.

- Among people in Nevada living in a food desert, 89 percent live in urban area and 11 percent reside in rural areas.

Food Desert Locator map of Nevada census tracts. The green census tracks are food desert low-income neighborhoods without easy access to a supermarket or large grocery store. (updated May 2014)

Consequences of Food Deserts Those

living in a food desert may have inadequate options to obtain fruits and vegetables and, consequently, may have difficulty meeting the Guidelines for Americans 2010, which recommends consumption of three or more fruits and vegetables daily, especially dark-green and red and orange vegetables (USDA, 2010). Moreover, food desert residents eating convenience store foods consume diets high in sugar fats and sodium, and low in whole grains (Johns Hopkins Public Health, 2014).

These diets are associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, the number one cause of death in the United States, and also diabetes, strokes, hypertension, and increased weight gain and obesity (Spence, Cutumisu, Edwards, Raine, & Smoyer-Tomie, 2009).

Influential Factors of Food Deserts

Beyond proximity and access to transportation to a supermarket, the consumer’s neighborhood retail environment is another factor influencing food purchases. Food price, quality, variety, preparation time, where people shop and the presence of culturally appropriate foods also impact what foods people purchase and the possible presence of a food desert (Odoms-Young, Zenk, & Mason, 2009 and Alkon, et al. 2013). Although study results vary, we are gaining an understanding of which factors are the most important in making food purchase choices.

One problem is the use of the 1-mile radius of store availability to define a food desert in cities. One mile might consist of 20 blocks and may not reflect a “reasonable shopping distance” for the elderly, for families with children or for those physically challenged.

People living in rural areas live, a median of 31/2 miles away from larger food outlets (Ver Ploeg et al., 2012) thus requiring access to a car or public transportation (Dutko, Ver Ploeg & Farrigan, 2012). Because of this, rural residents tend to stock up on nonperishable items at large outlets, such as Costco. If they do not have a car, they may carpool. In fact, 93 percent of people who live in lowincomefood desert areas who carpool (Ver Ploeg et al., 2012).

However, while transportation may seem to be the most significant deterrent to accessing healthful food, a survey indicated that 60 percent of consumers state that a grocery store that “provides good values for the money” was the most important factor in deciding where to grocery shop. Only 23 percent of consumers cited proximity to home as an important factor (Nielsen, 2007).

Food desert definitions impact residents differently. For example, in some large cities, such as New York, small food retail vendors specializing in bakery, cheese, meat, and fresh fruit and vegetables are still present. These specialty stores are not counted as large food outlets (Odoms-Young, et al., 2009), but they do provide healthful foods.

In the past, people in rural areas augmented their food sources with home grown food. Production of home grown fruits and vegetables has declined. For example, by the end of World War II, an astonishing 40 percent of all fresh vegetables consumed in the U.S. were produced in backyard gardens and community areas (Brown & Jameton, 2000). Even in rural areas where residents have historically gardened, hunted and fished for food, these alternative food souces have decresed (Smith & Miller, 2011). In addition, in single-parent households or households in which both parents work, the time available for food preparation decreases, encouraging the reliance on fast-food meals (Smith, Ng, & Popkin, 2013).

Potential Strategies

First Lady Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move!” Campaign is committed to reducing the number of food deserts across America at the local level over the next seven years. Several interventions and stimulants are being explored.

A multipronged approach to acknowledge not just limited access to supermarkets, but also the complex interaction of multiple barriers, is needed to decrease food deserts. Effective solutions need to be specific for each community. A one-size-fits-all approach does not address the different infrastructure failures in urban areas or rural areas. Therefore, engaging the community in the process to establishing potential solutions is essential. Some community actions to address food deserts are provided below. For additional information, see CDC.

Alternative food supply systems, such as community or home gardens, shares of community-supported agriculture (CSA) and farmers markets, offer a source of fresh fruits and vegetables at the local level.

- Educate residents on how to grow their own food. The University of Nevada, Reno Cooperative Extension offers the Grow Yourself Healthy, Food for Thoughts and Master Gardener programs.

- Entice farmers markets to participate in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program due to the high prevalence of poverty in food deserts. This is a major component in the Nevada Department of Health and Human Service Nutrition Action Plan.

- Increase demand of local small farm produce by connecting farmers to consumers such as local restaurants and farmers markets. The University of Nevada Cooperative Extension’s Producer to Chef Providesprovides a successful example.

- Support Food Bank of Northern Nevada’s mobile van that transports healthful, free foods to neighborhood areas of need.

- Establish public and private partnership agreements to bring private owned supermarts into underserved areas.

- Cultivate healthy options in local neighborhoods where residents purchase food, such as providing financial incentives for convenience stores to stock high-quality, culturally appropriate, inexpensive fruit and vegetables in readyto- eat packaging. Healthful foods must have a competitive value with salty highfat snack items.

Fresh local produce mobile van transports healthy, free foods to areas in need.

References

Brown, K.H. & Jameton, A.L. (2000). Public health implications of urban agriculture. J Public Health Policy, 21(1): 20-39.

Dutko, P., Ver Ploeg, M., & Farrigan T. (2012). Characteristics and influential factors of food deserts. USDA, Economic Research Service Report N. 140.

Odoms-Young A.M., Zenk S., & Mason M. (2009). Measuring food availability and access in African- American communities implication for Intervention and policy. Am J Prev Med, 36(4S):S145-S150. Nielsen Company. (2007). Good value is the top influencer of U.S. grocery store choice, Nielsen Reports. Schaumburg, Illinois: The Nielsen Company.

Spence, J.C., Cutumisu, N., Edwards, J., Raine, K.D., & Smoyer-Tomie, K. (2009, June). Relation between local food environments and obesity among adults. BMC Public Health, 9(192).

Smith, C., & Miller, H. (2011). Accessing the Food Systems in Urban and Rural Minnesotan Communities. J Nutr Educ and Behavior, 43(6), 492- 503.

Smith, L.P., Ng S.W., & Popkin B.M. (2013). Trends in US home food preparation and consumption: analysis of national nutrition surveys and time use studies from 1965-1966 to 2007-2008. Nutr J, 12(45), open access Nutrition Journal.

U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA], U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th Edition, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, December 2010.

Ver Ploeg, M. Breneman, V., Dutko, P., Williams, R., Snyder, S., Dicken, C., Kaufman, P. (2012, Nov). Access to affordable and nutritiousf Food: updated estimates of distance to supermarkets using 2010 data. ERR-143, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (2014a) Food deserts.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (2014b) Food deserts. Accessed 7.17.14.

Johns Hopkins Public Health (2014) Food Issue: what we grow, what we eat, what we seek. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Magazine.

Spears, K., Powell, P. and Kim, W. Y.

2014,

What is a Food Desert?,

University of Nevada Cooperative Extension, Fact Sheet-14-05