This publication is intended as a guide for potential growers interested in pomegranate production, as pomegranates are becoming highly marketable. The pomegranate serves as both a fruit crop and an ornamental and is well suited to the soils and climate of southern Nevada (Robison, 1981). Sample costs and returns to cultivate pomegranates in southern Nevada are presented here to help in the determination of economic feasibility and preparation of business and marketing plans. Calculations are based on typical production practices in the southern Nevada area and may not apply to every operation. An interactive budget will be available online at Cooperative Extension’s website, FOOD SAFETY.

Pomegranate Flowers

Assumptions

The following assumptions referred to in the attached tables reflect typical costs and returns associated with pomegranate production in southern Nevada. The practices described are not the recommendations of the University of Nevada, Reno, but rather production practices and materials considered typical of well-managed pomegranate operations in the area, as determined by consultations with local producers and the best available research. Costs, materials and practices are not applicable to all operations, as production practices vary among producers in the area. It is assumed that commercially viable fruit production begins the fourth year after planting. Capital outlay and expenses for years prior to full production are accounted for in establishment costs.

Establishment

LAND

The representative farm consists of 30 acres of land, with three acres dedicated to the cultivation of pomegranates. Land in southern Nevada rural agricultural areas in 2014 was valued at approximately $11,500 per acre. The farm had other ventures; the three acres of pomegranates utilized 10 percent of land and 20 percent of effort and other associated costs unless indicated otherwise.

SITE PREPARATION

The first step was to have the soil tested. This is important regardless of what was previously planted in the area under consideration. Soil analyses guided nutrient additions to be incorporated before planting. The ground was prepared for planting by custom ripping to break up the soil, improve water infiltration and allow for fertilizer penetration. On the representative farm in this example, organic matter in the form of well-composted dairy or steer manure was spread onto the field at a depth of 1 inch before the ripping was done so it was worked into the soil. For the 3-acre plot, this took approximately 37 cubic yards of manure at a cost of $25 per yard. It was then disked to prepare it for planting. The ripping and disking was a one-time custom hire expense. The cost of having this done was approximately $250 per acre for a total of $750.

Immature Pomegranate Fruit Forming

IRRIGATION SYSTEM

This representative farm had a well and pumped its own water for irrigation. The cost of drilling the well was approximately $40,000 and the purchase of the pump was an additional $2,000. A double line of tubing was run on each row with five flag emitters at each tree. There were 20 rows of pomegranates. Each row of 360 feet took two rows of tubing, one on each side of the trees, for a total of 14,400 feet, plus the 360 feet across the end of the rows. Approximately 14,760 feet of tubing and 1,500 emitters were needed as a minimum. A total of 15,000 feet of tubing was purchased. The cost of the irrigation tubing and emitters was $2,765.

CULTIVARS

While there are many different types and colors of pomegranates, the deep red are most well-known by consumers. The ‘Wonderful’ cultivar is the commercial variety most planted in southern Nevada and is used extensively for juices and jellies (Sauls, 1998).

PLANTING

The initial planting on this representative farm was 300 pomegranate trees, 100 trees per acre. It was assumed that there would be a 5 percent loss from irrigation issues or predation, leaving 285 producing trees. The spacing was 20 rows with 18 feet between rows and 24 feet between trees. Trees were purchased at $25 per tree for our estimates, but could also be propagated from cuttings to reduce replacement costs and will remain true to their variety. While pomegranates grow readily from seed, fruit from seed-grown trees will not be identical to the parent tree due to genetic combinations. To propagate and insure varietal accuracy, hardwood cuttings 8 to 10 inches long can be prepared from last year’s growth. They should be taken while the plant is dormant, dipped in #2 or #3 rooting hormone, and placed in a mixture of 40 to 60 percent perlite mixed with household potting mix, leaving about 3 inches of stem exposed above the mixture. The cuttings should be kept moist but not wet and kept above 60°F. They root in 8 to 16 weeks and can then be planted outside when weather conditions permits. Pomegranate trees thrive in calcareous, alkaline soils, in deep acidic loam and in a wide range between these soil types (Morton, 1987). While pomegranates perform well in deep, well-drained loam, they also grow well in sandy or adobe-clay soils and tolerate mildly alkaline conditions (Crites et al., 2004).

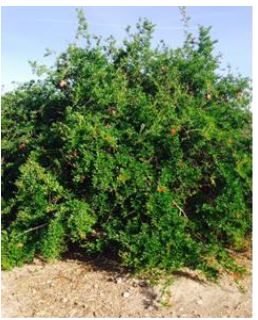

Young Pomegranate Specimen (left) Mature Pomegranate Specimen (right)

Production Costs

IRRIGATION

Irrigation through a drip system started in March and ran through November. Pumps typically ran five hours per day, three days per week, at a cost of $50 in utilities per month for the three acres. This irrigation approach allowed for the water to soak in deeply, forcing leaching of the alkaline salts commonly present in southern Nevada soils and helping the roots to penetrate further into the soil, protecting them from the surface heat and drought.

FERTILIZING

After the first year, fertilizing was typically done by top dressing 4 yards of well-composted manure for the 3-acre plot spread around the trees at a cost of $25 per yard.

PEST MANAGEMENT AND COSTS

For our representative farm, diatomaceous earth and Neem oil were applied yearly as a preventative measure to control insect pests. The diatomaceous earth had a cost of $1 per pound, and 50 pounds were required for the 3 acres for a total cost of $50. One quart of Neem oil was required at a cost of $25 for the 3-acre operation. The use of Neem oil and diatomaceous earth are considered organic pest repellants and so do not affect an organic certification if growers choose to obtain it. Aphids attack pomegranate trees, but can be controlled by natural predators such as lady beetles.

One pest that is common in southern Nevada on pomegranates is the leaffooted plant bug. It feeds on the arils, or seeds, causing them to wither. High numbers of bugs and damage to the fruit occur late in the season as the fruit ripens. They can be controlled with pyrethrum. Pyrethrum is a biological pest control categorized as a plant toxin insecticide. It is derived from chrysanthemum flowers and is one of the least poisonous insecticides to mammals. Methomyl will also work, but must be used very carefully due to its high toxicity to humans. When using insecticides, it is important to follow all label directions exactly (Grafton-Carwell, E. E. 2013). All split fruit should be removed and destroyed to minimize the population of the leaffooted plant bug by removing its food source. Weeds can be mitigated by mulching between the trees.

Leaffooted Plant Bug (Leptoglossus sp.)

LABOR

Labor costs included an onsite farm manager, whose duties consisted of weeding, pruning and maintaining the drip lines for irrigation. Labor time averaged one hour per acre per day. The pay for this position was $1,000 per month or $12,000 per year. This cost was separate from the harvesting, which occurred once yearly and employed hired labor paid by the piece at 25 cents per fruit harvested, which included field packing.

Pomegranate Orchard

FUEL AND LUBE

Fuel was calculated by hours of use for each piece of equipment. The breakdown is included on the bottom of the investment summary.

MAINTENANCE

Although maintenance costs vary from year to year, for this study, annual repairs on all farm investments or capital recovery items that require maintenance were calculated at 1 percent of the average asset value.

HARVEST

The fruits are ripe when they have a distinctive color and a metallic sound when thumped (MacLean et al., 2011). They must be picked before overly mature, at which stage they tend to crack open, inviting insect infestations. The cultivar ‘Wonderful’ ripens six to seven months after flowering. The fruit cannot be ripened off the tree. Growers listen for a metallic sound when tapped to gauge if the fruit is ripe and ready to pick (Morton, 1987). Trees normally start producing three to four years after planting. To harvest the fruit, the stem was cut off as near to the fruit as possible to avoid rubbing or poking and injuring other fruit when packed into storage containers.

Pomegranate Reaching Maturity

YIELD

As the tree matures, it should produce more fruit. According to research from Texas A&M, production in the fourth year may amount to 20 to 25 fruits per tree (Stein et al., 2010). By the 10th year, the trees should be established, and production typically increases to 100 to 150 fruits per tree (about 50 pounds). In a well-managed orchard, the average annual yield can be as high as 200 to 250 fruits per tree, or about 75 pounds (Stein et al., 2010). For this representative farm, we used a sellable yield of 150 fruits per tree. Historically, yields in a well-managed orchard in the Moapa Valley can be exceptional. In 1968, pomegranate trees were planted at the Southern Nevada Experimental Station in Moapa Valley. By 1979, they were yielding an average of 190 fruits, or 130 pounds per tree. Since 1990, there has been no maintenance for the pomegranates except sporadic watering. In 2012, these trees were 44 years old. Harvests from a sample tree yielded 403 fruits with a weight of 179.8 pounds. With a lack of maintenance, fruit size diminishes. There are documented examples of living pomegranate trees in Europe that are over 200 years old. Yet, their vigor begins to decline after 15 years (California Rare Fruit Growers, 1997).

PACKAGING AND MARKETING

All fruit from the representative farm used in this example were field-packed into boxes. They were packaged 25 to 30 fruits per box, depending on pomegranate size. Fifteen hundred boxes were needed at a cost of $1 each, for a total cost of $1,500 excluding labor. During the fall, pomegranates were sold off the farm, to local grocery stores, at farmers markets, at the yearly Pomegranate Festival in Moapa Valley, and at other local events. Advertising was done with signs in front of the farm during the selling season, ads in the local paper, and banners at the farmers markets. This publication shows returns from individual whole fruit sales. Local growers also include large-scale operations that sell juice wholesale and small cottage food producers that sell jam and jelly varieties on the retail market direct to the consumer at festivals and fairs.

KEEPING QUALITY AND STORAGE

Pomegranates store well, very similar to an apple. They are best stored at 32 F to 41 F (0 C to 5 C). When refrigerated whole in plastic bags, they will keep up to three months. The arils or seeds can also be frozen for long-term storage. The fruit quality improves in storage, becoming juicier and more flavorful.

Ripe Pomegranate

Fixed Costs

CAPITAL RECOVERY COSTS

Capital recovery costs are calculated on machinery, equipment and capital improvements to the land. They are accounted for in their respective categories. Capital recovery costs are the amount the grower must recover annually through annual depreciation of all the farm investments less the salvage cost at the end of the item’s useful life. These amounts should be set aside each year so the funds are available to replace items as they wear out. They are calculated using straight line depreciation. Machinery depreciation time periods are based off IRS Publication 946.

COMPUTATIONS

Average Asset Value Computation:

(Purchase Price + Salvage Value) divided by 2

Salvage Value

Salvage value is 10 percent of the purchase price, which is an estimate of the remaining value of an investment at the end of its useful life. Land does not lose value and therefore does not depreciate.

Straight Line Depreciation Computation:

(Purchase Price + Salvage Value) divided by Useful Life

WHOLE FARM INSURANCE

Whole farm insurance is a new crop-neutral revenue insurance product for diversified farming operations. Unlike traditional yield or revenue insurance, this product is not intended for a single specific crop, but for all the crops and livestock grown or raised on a given farm. Our cost of $150 was for the portion allocated to the pomegranate operation.

MACHINERY AND VEHICLES

Machinery and vehicle costs included annual capital recovery costs, property insurance and property taxes. Property insurance provided coverage for property loss and was charged at 0.8% of the average asset value. Property taxes were estimated at one percent of average asset value. Repairs and fuel were considered variable costs and reported there.

EQUIPMENT

Equipment costs included annual capital recovery costs, property insurance and property taxes. Property insurance provided coverage for property loss and was charged at 0.8 percent of the average asset value. Property taxes were estimated at 1 percent of average asset value.

LAND CHARGES

Land charges included annual capital recovery costs, property insurance and property taxes. Property insurance provided coverage for property loss and was charged at 0.8 percent of the average asset value. Property taxes were estimated at 1 percent of average asset value.

MANAGEMENT

Management included various administrative expenses paid out over the course of the year. These included accounting and legal expenses of $100 for tax preparation, and office and travel expenses of $250 for recordkeeping and marketing.

OTHER COSTS

A complete listing of farm investments and associated costs can be found in the following spreadsheets.

*Tables here

References

- California Rare Fruit Growers. “Pomegranate Fruit Facts.” 1997. Online. Available at Pomegranate Fruit Facts

- Crites, Alice, et al. “Growing Pomegranates in Southern Nevada.” University of Nevada Cooperative Extension, 2004.Publication FS-04-76

- Grafton-Cardwell, E. E., et al. “Pomegranate Leaffooted Plant Bug.” UC IMP Pest Management Guidelines. Online. Available at Pomegranate Leaffooted Plant Bug

- LaRue, James H. “Pomegranates.” Farm Advisor, Tulare County, 1980. Online. Available at Pomegranates

- MacLean, Dan. “Pomegranate Production.” University of Georgia Cooperative Extension. Online. Available at Pomegranate Production

- Morton, Julia F. “Pomegranate.” Fruits in Warm Climates, 1987. Online. Available at Pomegranate

- National Pesticide Information Center (NPIC), “Pyrethrins & Pyrethroids.” 1998. Online. Available at Pyrethrins & Pyrethroids

- Robison, Dr. Gayland D. “Report on Work at the Southern Nevada Field Laboratory.” Agriculture Experiment Station, 1981. University of Nevada Reno. Southern Nevada Field Laboratory Publication R143.

- Sauls, Julian W.,” Home Fruit Production-Pomegranate.” Texas Citrus and Subtropical Fruits, 1998. Online. Available at Home Fruit Production-Pomegranate

- Stein, Larry, Kamas, Jim, and Nesbitt, Monty. “Pomegranates.” Extension Fruit Specialists, the Texas A&M University System, 2010. Online. Available at Pomegranates