In this edition

- A Note From the Editors

- Washoe County Master Gardener Coordinator

- What's Happening This Spring?

- Humble Bumble Bees

- Know Your Beneficial Predators

- Kokedama: A Great Kick-Off for a New Year

- A Mustardy 2023

- Worried About Weeds?

- Thoughts on My Garden

- A (Not So Secret) Garden for Teaching and Learning

- Master Gardener Photos

About This Newsletter

Welcome to our newsletter dedicated to gardening enthusiasts in Nevada! Here, the Master Gardener Volunteers of Washoe County are committed to fostering a community of gardening knowledge and education. Through this publication, we aim to provide research-based horticulture insights for our readers. Each quarter, we offer a wealth of information covering various aspects of gardening, from upcoming garden events to advice on topics ranging from pest control to sustainable gardening practices. Join us as we explore the science and artistry of gardening together!

A Note From the Editors

Daffodils popping up, a sure sign of spring!

Photo by Becky Colwell

Welcome to the first issue for 2024!

We have a couple of informative articles on weeds to help you get a better handle on them before they take over your yard. Remember the No. 1 rule in weed control: Don’t Let Them Produce Seeds!

Insect pests might be another big problem this season as we didn’t have a very cold winter. Many predatory insects can help control these pests, so check out the beneficial predators article and learn what they look like.

On the fun side, learn how to make a kokedama, or Japanese “moss pot,” and review the latest developments at the teaching and demonstration garden at Rancho San Rafael Regional Park in “A (Not-So-Secret) Garden.”

The Master Gardener program is also providing garden talks and mobile help desks this year, and the annual plant sale is coming up. “What’s Happening This Spring” has more detailed information.

We hope you enjoy this issue!

Becky, Chris, and Sara

Washoe County Master Gardener Coordinator

Extra! Extra!

Photo of Master Gardener, Mimi Richards.

You heard it from our editors, Welcome to our first edition of the Extension Washoe County Master Gardener Newsletter! Our goal is to share our passions with you!

If you are unfamiliar with Master Gardeners, let me tell you a little bit about them. They are an amazing group of educational volunteers who have an intense passion for horticulture and supporting their community. When this is partnered with the University of Nevada Reno, Extension it creates a platform for university-backed, scientifically researched horticultural activities, demonstrations, and hands-on activities to meet our community’s needs. They are people who live here and play here, right beside you, and most importantly, they garden here. If you have a question about horticulture, they can find the answer.

Cultivating Gardens and Communities! You may see them giving a talk or demonstration at a local school, library, or park. They partner with other entities like Soulful Seeds, The Northern Nevada Veterans Home, The Northern Nevada Bee Conference, and the Ronald McDonald House for educational events. They are at Home Show, Field Day with UNR, and Washoe Valley Days. They help with sales days for The Washoe State Tree Nursery. They have demonstration gardens at Rancho San Rafael Regional Park and The Pioneer Center for the Performing Arts. They are part of a northern area Annual Garden Tour and host an annual seedling sale, with plants grown by Master Gardeners. And honestly, so much more. If you look, you will find them.

They are amazing people. I am so fortunate to be able to work with them. I hope you enjoy the newsletter. Look for it every quarter.

Feel free to reach out to me directly with questions or comments, at rmcclure@unr.edu.

Rachel McClure, Washoe County Extension Master Gardener Coordinator.

What's Happening This Spring?

Master Gardeners will be giving short presentations on a wide range of gardening topics at various locations this spring, and a mobile Master Gardener help desk will be available at some locations as well.

See Locations, dates, and times below.

Garden Talks at the Library

Where: Spanish Springs Library, 7100A Pyramid Way, Sparks

Talks will be held monthly on the second Sunday from 1 to 3 p.m., and the mobile help desk will be available at the same location from 1 to 4 p.m.

March 10, 2024

- Cool Season vs. Warm Season Crops: You want to start a vegetable garden, but what should you plant, and when? Come join Linda Fulton, Master Gardener, to learn what you can get in the ground now, and what should wait for warmer temperatures.

- Reading Seed Packets: Those seed packets offer more than a pretty picture. They’re chock full of information about the variety, whether it’s a one-season-only plant or will come back next year, whether you should start it inside or plant it directly in the garden, and how long it will take to bloom or be ready to eat. At this hands-on class, Shari Elena Quinn, Master Gardener, will give you a seed packet and tell you how to decipher it.

- Starting Seeds: Want to get a head start on the harvest? Some vegetables are best planted as seedlings rather than seeds to make sure they ripen before our short season comes to an end. Learn what to start indoors and when, and how to transplant the young plants outdoors, with Beth Heggeness, Master Gardener.

April 14, 2024

- Spring Grass Care: Thoughtful care of your grass in spring can help it survive the heat of the summer and thrive throughout the growing season. Get the tips from Judi Kleidon, Master Gardener.

- Creating a Cutting Garden: Grow your own fresh flower bouquets! Deborah Henderson, Master Gardener, gives guidelines to planning, growing, maintaining, and harvesting plants to have a continuous supply of fresh cut flowers and foliage all season long.

- Creating a Moonlight Garden: A garden that glows white under the light of the moon is a singular summer treat. Victoria Gutierrez, Master Gardener, shows the main elements of a moonlight garden, and how best to use available space. She also offers a list of suitable plants.

May 12, 2024

- Native Bees and How to Host Them: Native bees are the unsung heroes of pollination, as they are more efficient pollinators and start earlier in the season than honeybees. Nevada has more than 1,000 species of native bees. Learn how to make them welcome in your garden and yard with Chris Doolittle, Master Gardener.

- What Colors Attract Specific Pollinators: What does a pollinator see in a plant? More than you might think. And plants that want to be noticed take care to be alluring. Learn about pollinators, the biology of their sight, how plants attract them, and which colors draw in specific pollinators. Master Gardeners Deb Barone and Kathi Linehan delve into this fascinating topic.

- Gardening with Herbs: Many herbs can be grown in our area in containers, garden beds, and as landscape plants. Come learn about the herbs that grow best in our climate and hear some tips to keep them happy and productive from Leslie Edgington, Master Gardener.

Third Thursday Evening Garden Talks

Where: Rancho San Rafael Regional Park, 1595 N. Sierra St., Reno

Join Washoe County Cooperative Extension Master Gardeners on the third Thursdays in June, July, August, and September for evening garden talks. Talks will be held in the park’s community garden, beginning at 6 p.m. and ending by 7:30 p.m. The talks are hands-on, casual, informative, and free.

Topics planned for Thursday, June 20, include the following:

- A Nevada Story: The History of the Rancho San Rafael Community Garden

- Be Gone Bug: Northern Nevada’s Common Garden Pests

- More Than Just Bees: Pollinators in the Garden

Also on display during the garden talks will be the Nevada Weed Education Station with examples of weeds present in the garden during the month of June.

Master Gardener Annual Plant Sale

Held at the extension office, 4955 Energy Way, Reno

Friday, May 17 – 2 to 6 p.m.

Saturday, May 18 – 9 a.m. to 1 p.m.

Humble Bumble Bees

Photos and article by Becky Colwell

Early spring queen Bombus nevadensis (Nevada bumble bee)

foraging in Caragana aborescens (Siberian peashrub) flowers.

As my spring shrubs and perennials start blooming, I anxiously await the arrival of large queen bumble bees. Some years I have a variety of species visiting while other years I see only a few. Their name stems from the Middle English word bombelen, meaning “to hum,” for the low buzzing sound they make while flying.

Because of two special physical adaptations that allow them to withstand cooler temperatures, queen bumble bees are among the first bees sighted in early spring and the last to be seen in late fall. The first adaptation is their ability to absorb the sun’s energy when basking due to their thick and insulating coat of hair. Secondly, they have the ability to generate heat by unhooking their wings from their flight muscles. This allows them to internally “shiver” those muscles, to generate heat, without moving their wings.

A queen B. nevadensis visiting Allium campanulatum (Sierra onion) at Huffaker Hills.

Of the 250 known bumble bee species worldwide, only about 50 are found in North America. They are generalists, which means they forage on a wide variety of flowering plants. Studies have found that crops pollinated by bumble bees produce bigger fruit and have faster fruit set and larger yields. They are especially successful in pollinating plants in the Solanaceae family (tomatoes, potatoes, peppers, eggplant) because of their ability to “buzz” pollinate. Members of the Solanaceae family keep their pollen inside anthers, which function like salt shakers. The pollen comes loose only when the anthers are turned upside down and shaken. Buzz pollination does just that! The bumble bees hang below the flower and “buzz” their flight muscles to shake the pollen loose. This is why large greenhouses use bumble bees as the primary pollinators for their crops.

Queen B. morrisoni (Morrison bumble bee) demonstrating the ability

to hang upside down while collecting pollen from my Symphytum grandiflorum

‘Hidcote Blue’ (a hybrid comfrey).

Most bumble bees are ground nesters, making their homes in abandoned rodent burrows, piles of wood or piles of leaf litter. One of the coolest facts about them is that they are the only semi-social native bee in the United States.

A possible bumble bee nest. Being ground nesters, they look for

abandoned rodent cavities, holes in building foundations or stacks of firewood.

Semi-social means they have a colony during the summer months and then become solitary during the winter months.

Here’s how it works: When the young queen comes out of hibernation in the spring she looks for a nest, which needs to have several cavities, such as an abandoned mouse or other rodent nest. Inside the nest she starts preparing for her brood by building wax pots that she fills with pollen and honey. Then she builds a bigger cell for her brood. In early spring, the bumble bees you see are the queens foraging to get their nests ready for egg-laying.

Notice this queen B. vosnesenskii (Vosnesensky or yellow-faced bumble bee)

foraging to fill her pollen sac and ready her nest.

Once her nest is readied, the queen begins laying her first brood, about six eggs that will become sterile female worker bumble bees. Until these workers emerge, the queen will continue to forage. After the workers take over foraging, the queen remains in the nest laying eggs while the workers take care of everything else to keep the nest alive.

This worker B. vosnesenskii is busy foraging on my

Perovskia atriplicifolia (Russian sage). Notice the pollen sticking to its hair.

As summer begins, the bumble bees we see are the workers, which are smaller than the queen. The life span of a worker bumble bee is only a few months. All summer long the queen stays underground laying eggs to add workers for the survival of the nest. The colony can grow to about 200 worker bumble bees through the summer.

A worker B. sylvicola (forest bumble bee) visiting my

Caryopteris x clandonensis (blue mist spirea). This was a rare visitor to my garden in 2019.

A worker B. bifarius (two-form bumble bee) foraging in my

Scabiosa spp. (pincushion flower).

When summer is ending, the queen lays male eggs as well as female eggs. These female eggs become queen bumble bees and will mate with the male (drone) bumble bees. All of the worker bees, the old queen, and the drones will die at the end of summer. Only the recently mated queen bumble bees remain and will sleep in secluded hideaways through the winter. In the spring, those queens emerge and start establishing their colonies for the next generation of bumble bees.

References:

- Koch, Jonathan, Strange, James, & Williams, Paul; “Bumble Bees of the Western United States,” U.S. Forest Service and the Pollinator Partnership.

- Wilson, Joseph S. & Carril, Olivia Messinger; “The Bees in Your Backyard,” 2016, Princeton University Press

Know Your Beneficial Predators

Photos & article by Becky Colwell

Adult lady beetle on Asclepias speciosa (showy milkweed) flower buds with aphids on the leaves.

Your garden is coming to life, and that means both flora and fauna. But don’t panic at the insects you see crawling on your plants. Only 1 percent of insects are actually pests, and they all have predators. Many of the insects visiting your flowers are eating the pollen and nectar they provide, while others are gobbling up the pests. Known as predatory beneficials, these insects work hard at keeping your plants pest-free (and they do it organically). Let’s get to know a few of these predatory beneficials.

Aphids, a very common pest visitor to our gardens, have many predators, the lady beetle being one. Most of us call it the lady bug, but technically speaking it is in the beetle family, not the true bug family. Aside from aphids, lady beetles will also eat mealy bugs, spider mites, the larvae of elm-leaf beetle, and many other soft-bodied insect pests. Lady beetles won’t stay around if you do not have any of these pests to eat, so it is best to let them naturally find you instead of purchasing them. And they will find you. When I volunteered in the Grow Yourself Healthy Program at Mariposa school gardens we had a very serious aphid infestation on the peach tree in the school garden. Almost all the leaves had been eaten. But we did notice a few lady beetles and their larvae so we waited a week before taking any action. When we came back the following week the peach tree was covered with lady beetle larvae and not many aphids were detected. The leaves all grew back and the peach tree yielded a plentiful crop.

Lady beetles go through complete metamorphosis; egg, larva, pupa, adult. Knowing how to identify them in all their stages is important so they are not misidentified as a pest.

Three lady beetle larvae on Chamaebatiaria millefolium (fern bush) leaves.

A newly hatched lady beetle larva eating an aphid.

Lady beetle larva getting ready to pupate.

Lady beetle pupa stage.

Since they overwinter as adults, lady beetles are ready for action in spring when plants begin to green. Females lay their eggs in clusters under leaves near aphids so the larvae have a banquet as soon as they hatch. The larval stage lasts about three weeks, during which each larva will consume about 400 aphids. They then pupate from three to 12 days before emerging as adult lady beetles. Adults live from two months to over one year. Definitely a good predator to have around.

Adult green lacewing resting on a Viburnum lentago (nannyberry) leaf.

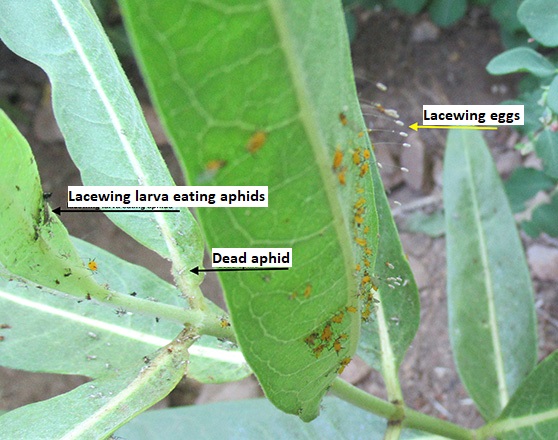

Another great insect predator to have in your garden is the green lacewing. Although the adults feed on nectar and pollen, they are predators in their larval stage. When inspecting your plants, keep a lookout for adults and their eggs -- small white capsules at the end of a stalk. The eggs hatch in four to 10 days.

Lacewing eggs attached to an Asclepias speciosa

leaf covered with aphids, food for when they hatch.

Lacewing larva using its sucking mouthparts to drain

the fluid from an aphid. This aphid lion will eat up to 200 aphids before pupating.

Known as aphid lions, lacewing larvae look similar to lady beetle larvae except for their lighter coloring. They are ravenous predators, feeding on aphids, leafhoppers, spider mites, thrips, and many other soft-bodied insect pests. The larval stage lasts two to three weeks. Lacewing cocoons looks like small white silken balls hidden on a plant. In about one week the adult emerges. Adult lacewings live from one to three months and will stay in your garden, laying more eggs, if you continue to provide flowers for the nectar and pollen they need. In cold regions like ours, lacewings overwinter as pupae in leaf litter or other protected locations.

Adult male snakefly on Asclepias speciosa leaf.

Notice the elongated prothorax (neck) and flattened head.

Snakeflies are not commonly seen in the garden, but if you spot one, be reassured that they are very beneficial. Like lady beetles, both adult and larval snakeflies are important predators of small, soft-bodied insects, aphids, caterpillars, and mites. Their name comes from the elongated prothorax (neck) and flattened head, which resembles a snake. This flexible neck allows them to raise or turn their heads without turning their whole body. They are closely related to the lacewing and are found only in western North America.

Adult female snakefly on Helianthus maximillan ‘Santa Fe’. The ovipositor

is a tubular organ used to deposit clusters of eggs in bark crevices or other hidden areas.

A big reason we don’t see many adult snakeflies in our garden is that their very long life cycle -- egg, larva, pupa, adult -- takes two to three years to complete. The larval stage is spent under bark or in leaf litter, where they most likely eat soft-bodied insects like wood borer larvae and codling moth larvae. I find it very exciting to spot a few snakefly adults in my garden.

Adult syrphid fly warming up on a sidewalk. Don’t be fooledby its bee or wasp-like

coloration. It is a fly as indicated by the short antennae, large eyes and only one set of wings.

Another spring emerging insect predator in our gardens is the syrphid fly, commonly called flower fly or hover fly. Adults can be seen hovering in midair around flowers, eating nectar and pollen.

A syrphid fly “hovering” near an iris.

This common behavior gives them the nickname “hover fly.”

Like the green lacewing, it’s the larval stage of the syrphid fly that is the predator. The adults lay their small, oblong white or gray eggs next to aphid colonies. The larvae look like caterpillars with a tapered body. In seven to 10 days, after consuming large quantities of aphids, the larvae will fall to the ground and pupate in the soil. If the adults have a continuous supply of flowers, they can have several generations per year. Depending on the species, they overwinter as either pupae or larvae in leaf litter.

An adult robber fly on my Prunus virginiana

(Western chokecherry) waiting for an unsuspecting insect.

Lastly, the robber fly is another insect predator that shows up in spring. The adults are not particular as to what insect they hunt, feeding on wasps, bees, dragonflies, grasshoppers, other flies, and even some spiders. Their importance to our gardens is in keeping a healthy balance between insect populations in various habitats. One distinguishing characteristic of the robber fly is its long legs that aid in the capture of their prey in mid-air. Once the prey is captured, the robber fly injects it with enzymes that immobilize it while turning its insides into a liquid meal. Most of the flies have black, gray, or brown coloration and are particularly abundant in arid and sunny habitats.

Adult robber fly under the leaves of my

Caragana aborescens (Siberian peashrub) waiting for a pollinator meal.

The whitish-colored eggs are laid in masses on low-lying plants or in crevices within soil, bark, or wood. The larvae live in naturally decaying organic material in the soil and feed on eggs, larvae, or soft-bodied insects. They overwinter as larvae and pupate in the soil. Depending on the species of robber fly, their life cycle can take from one to three years.

Lady beetle larva on climbing rose bud with aphids.

Be patient when you see those aphids this spring. Let lady beetles, lacewings, and other garden protectors be your first choice for pest control. The 99 percent of insects that are harmless or beneficial insects will thank you for not using chemicals on your plants.

References

- Borror, Donald J. and White, Richard E.; “A Field Guide to the Insects of America North of Mexico,” 1970, Houghton Mifflin Company Boston.

- Colorado State University Extension; “Beneficial Insects and Other Arthropods,” Fact Sheet No. 5.550, Insect Series, Home and Garden, 2009.

Kokedama: A Great Kick-Off for a New Year

Article by Liz Morrow

Liz Morrow shows a kokedama to residents of Atria Senior Living.

Photo by Sharon Fabbri

As a Master Gardener volunteer, have you noticed how non-Master Gardeners assume that you must know everything about plants and gardens? Often, I am asked about something that I am truly challenged to answer. And that’s one of the things that is so great about being a Master Gardener. Recently, I was asked back to help the residents at Atria Senior Living with an activity regarding kokedama. “Koke -- what?” The research began…

Kokedama roughly translates from Japanese to “moss ball.” It’s a beautiful way to create a planting pot using natural materials. Sure, I can help seniors make a wet soil medium, shape it into a ball, stick a house plant in it and then wrap it in moss while holding it all in place with twine.

Sounds fun. And you know what? It was. I asked a new Master Gardener volunteer, Sharon Fabbri, to join me in this opportunity. She gladly did and was a hit with the residents.

It isn’t really known when Kokedama began, although it is believed that it was a way for the lower-income class in Japan during the Edo period (1603-1868) to enjoy bonsai without having to have an expensive pot for the plant.

The word symbolizes health, balance, zen energy, beauty, and peace -- great symbolism for beginning a new year.

How to Make Kokedama

To make a kokedama, you’ll need potting mix, peat moss, sheet moss, twine (or string), a plant and a saucer for display (or you can hang the plant, using the string that binds the ball).

- In a container or bowl, make a mixture of half potting mix and half peat moss and thoroughly water until it is almost the consistency of mud.

- Fill another container with water and soak your sheet moss.

- Once that is done, ball up the soil as you would to make a snowball, squeezing out as much of the water as possible. Shape the soil mixture into a nice round ball. Toss the ball up lightly into the air. If it holds its shape when you catch it, you’re ready for the next step.

- Divide your ball in half and set it aside.

- Grab your plant and remove as much of the soil as possible from the roots, then place the plant between the two halves of the ball.

- Take the sheet moss that has been soaking and wrap the root-filled part of the ball, excluding the leafy part of the plant.

- Wrap the twine around the top of the ball, below the plant, tie a knot, and then wrap the twine around and around the moss ball until you are satisfied it is secure. Then tie off the twine.

Sharon Fabbri demonstrates how to make a kokedama.

Photo by Liz Morrow

Voila! You now have your own kokedama.

A finished kokedama.

Photo by Liz Morrow

To care for your kokedama plant, soak the entire moss ball (not the leaves of the plant) in a bowl of water for 10 to 15 minutes. When there are no air bubbles bubbling up in the bowl, your plant is well-watered. Watering depends on the type of plant and where it’s growing (sun or shade, protected or breezy spot). You’ll know it’s time to water the ball if it feels extremely light when you lift it. Start with five to seven days out after preparation of the moss ball and adjust accordingly.

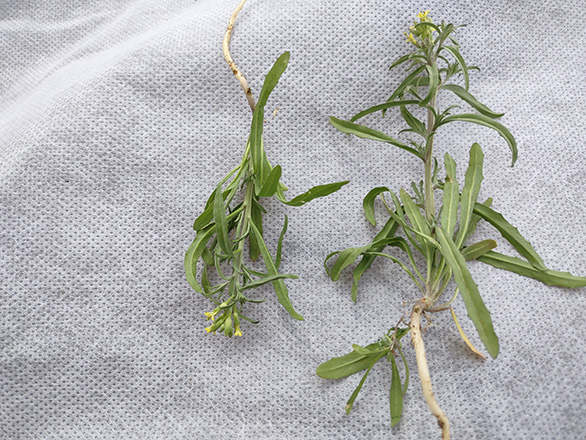

A Mustardy 2023

Photos & article by Martha McRae

Blue Mustard/Musk Mustard: Chorispora tenella

Spring came late to Reno-Sparks in 2023, but after a wet winter, the weeds made up for lost time. This article briefly discusses the mustards, weeds in the family Brassicaceae (formerly Cruciferae), that I identified during last year’s growing season at the Rancho San Rafael Community Garden.

As a reminder, a weed can be any plant growing where it is not wanted, but Nevada has lists of weeds considered noxious[1] and nuisance[2]. The mustards discussed here are listed alphabetically by scientific name.

Blue mustard (Chorispora tenella) is a winter annual weed that germinates in the late fall and overwinters until early spring before blooming. It can grow six inches to two feet tall, depending on conditions. It has a shallow taproot and small pinkish-to-purplish flowers of four petals that form a cross. The blooming period lasts two to three months from midspring to midsummer. Because it reproduces by seed, it is important to remove this weed before seed pods are formed. Blue mustard is also called musk mustard, because of its unpleasant odor; if eaten by dairy cows it will impart an unpleasant taste to the milk produced. Blue mustard is listed as a nuisance weed in Nevada.

Fixweed: Descurainia sophia (Not to be confused

with Descurainia pinnata - Tansy Mustard.

Flixweed (Descurainia sophia) is a winter annual or biennial with a short taproot and small, four-petaled yellow flowers. It sprouts in fall or early spring and reproduces by seeds. Seeds can be spread by wind, water, machinery, or animals, but most seeds are dropped on the ground near the plant. The resulting seed bank can be huge: A single plant produces 75-650 seeds, on average, but a large plant may produce upward of 700,000 seeds. Flixweed seeds have around a 70 percent germination rate and can remain viable in soil for up to three years, so preventing seed production is critical for control. Flixweed is toxic to livestock when ingested in large quantities or over a prolonged period of time. Flixweed is listed as a nuisance weed in Nevada.

Hoary Cress: Lepidium sp. (formerly known as Cardaria sp.)

Whitetop (not to be confused with tall whitetop/perennial pepperweed, Lepidium latifolium) is the generic name given to several weedy plants in the genus Lepidium (previously Cardaria). Three of these species are found in Nevada, the most prevalent being hoary cress, L. draba. The others are lenspod whitetop (L. chalapensis) and hairy whitetop (L. pubescens.) All three are native to Eastern Europe and Western Asia, and most likely came to the United States in the early 1900s in contaminated alfalfa seed from Russia (Turkestan), though some resources indicate whitetop may have been introduced as early as the mid-1800s. All three species of whitetop found in Nevada are listed as noxious weeds.

Hoary cress is a long-lived rhizomatous winter perennial, blooming in early spring. It has a deep, spreading root system, which makes hand-pulling generally ineffective. A single hoary cress plant with no competition can spread over a 12-foot area in one year, which can result in the establishment of a monoculture. Eradication by pulling or digging requires complete plant removal starting within 10 days after weed emergence and continuing throughout the growing season for a period of two to four years. Any roots left in soil can form new plants.

Perennial Pepperweed: Lepidium latifolium

Perennial pepperweed, also known as tall whitetop, is another long-lived perennial weed native to Eurasia. It came to the United States as an ornamental plant but ended up spreading throughout the West. It thrives in areas that remain damp to wet for the majority of the growing season and does well in both alkaline and salty soils. Because of its pervasiveness in irrigated areas and along stream banks and riparian areas, it is listed as a noxious weed in Nevada.

Perennial pepperweed can grow to six feet in height and spreads by both roots and seeds. It has a creeping root system that is both broad and deeply taprooted, making it more difficult to manage by mechanical means once it has grown past seedling stage. Seedlings emerge as a rosette on the root crown, and by the time the plant has six to eight leaves, buds have already developed on the roots. These buds can appear about an inch apart, resulting in hundreds of buds that may eventually develop shoots. (A piece of root as small as one inch long and 0.1 inches in diameter left in the soil after weeding/tilling may contain a bud capable of becoming a new plant.) It is easy to see how a single plant can develop into a large, dense patch of perennial pepperweed displacing desirable vegetation.

To make matters worse, seed production is high for perennial pepperweed -- up to 3,000 seeds per inflorescence. While seeds are thought to live only one to two years in the soil, they germinate readily (up to 95 percent of the seeds may be viable) and they don’t require a period of dormancy. They will sprout immediately if soil moisture and temperature conditions are suitable.

Clasping Pepperweed: Lepidium perfoliatum (Clasping Pepperweed

in the middle of a patch of another winter annual weed, bur buttercup).

Clasping pepperweed (Lepidium perfoliatum) is an annual or biennial with a short taproot and tiny white to yellow flowers. It reproduces by seeds that can be spread by wind, so prevention of seed production is critical for control. I was unable to find data on seed viability or germination rate, but it is pervasive enough to be listed as a nuisance weed in Nevada.

Tumble Mustard: Sisymbrium altissimum.

Tumble mustard (Sisymbrium altissimum), also called Jim Hill mustard, is a winter or summer annual, though it may sometimes be biennial. Native to Europe, it has naturalized throughout the United States and is listed as a nuisance weed in Nevada.

Tumble mustard reproduces by seed, which germinates to form a deeply lobed leafed rosette that resembles a dandelion. While it starts out ground-hugging, as it matures to the flowering stage, it becomes a bushy, branching plant that can grow to a height of five feet. It has a thick taproot and is a prolific seed producer. When the plant dries out, it breaks off and tumbles in the wind, effectively spreading its seeds as it goes. Seeds are long-lived in the soil, so preventing seed production is essential for control.

Unknown Mustard.

This weed is most likely a winter annual, as it was popping up with other winter annual weeds at the garden site. It has a short taproot and a flower consisting of four yellow petals in the cross configuration common among mustards. While it is definitely a Brassicaceae, it is not one of the yellow-flowering mustards listed as nuisance or noxious weeds in the Nevada weed field guides. Master Gardener Chris Doolittle did some research (because I went to the office and asked a Master Gardener) and she thinks it may be in the genus Erysimum. If anyone knows what it is, please let us know.

- In Nevada, a noxious weed is a plant that has been identified by the state as harmful to agriculture, the general public, or the environment. Property owners whose land is infested with noxious weeds are required to undertake control methods to prevent their rapid spread.

- These are weeds that are troublesome but have not been listed by the state as noxious.

Worried About Weeds?

By Carrie Jensen

UNR Extension Urban IPM and Pesticide Safety Program Coordinator

A dandelion sprout coming up after the snow melt in February.

Photo by Carrie Jensen

It may seem early, but weed season is already upon us. With cycles of wet followed by warm weather, we’re already seeing some weeds starting to germinate in February. That means it’s time to get a jump on weed management before it gets out of hand.

Integrated pest management (IPM) can help!

Here are three simple IPM techniques that will help prevent and manage weeds this spring:

1. Try sheet mulching

Disturbed bare soil is a weed’s best friend! The first line of defense is to cover the soil and prevent weed seeds from getting established. While there are many types of mulches to consider, sheet mulching (also known as lasagna composting) can be a great method to cover existing weeds and prevent the establishment of new ones.

This method uses layers of different mulch materials to shade out annual weeds and weed seeds. You layer the materials in the following order:

- Layer 1: 2-3” compost

- Layer 2: cardboard (overlap the edges)

- Layer 3: 2-3” compost

- Layer 4: 2-3” organic wood bark mulch

Wendy Hanson Mazet, UNR Extension’s community plant health

program coordinator, demonstrates how to sheet mulch around a tree.

Photo by David Harrison

Not only does this method block weeds, but as the layers of compost, cardboard, and mulch break down, they also add organic matter to the soil, which helps build healthy soils. This is another major IPM concept that helps prevent pests and disease over the long term. So, you reduce weeds now and build healthy soils for the future. That’s a win-win!

For more detailed instructions on sheet mulching, check out https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4r-CGtMP7pw. It shows how to use sheet mulching to remove lawn around a tree, but the same methods can be used for weed management.

2. Plant competition

If you’re not covering the soil with mulch to prevent weeds from coming in, the next thing to consider is beating them to the punch with desirable plants. If plants are already established, weeds won’t have space and resources to take hold.

- Consider seeding large areas of bare soil with erosion control or crop rotation seed mixes. Check with local seed suppliers to find the appropriate mix for your location. No matter where you source seed from, make sure that it is free of noxious weed seeds.

- Plant container plants in smaller areas. Keep plantings dense so that they will cover the soil once mature.

A native erosion control seed mix was applied on slopes in this

housing development to reduce the potential for weed invasion after construction.

Photo by Carrie Jensen

3. Reduce the spread of weeds

The saying goes, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” That is definitely the case with weeds! You can reduce headaches for yourself and recreational land managers if you stop the spread of weeds.

- Always buy weed-free gravel and wood chips. The Nevada Department of Agriculture's Noxious Weed Free Certification Program can direct you to suppliers of products free of noxious weed seeds.

- When you do yard work, always make sure to properly bag and dispose of invasive weeds. For a list of noxious weeds that you are required to control on your property, see the Nevada Noxious Weed List. If you need help identifying a weed, use the Nevada Noxious Weed Field Guide or contact your local Extension office.

- Be sure to clean boots and tires after you’ve visited areas with weeds.

- If you see invasive weeds, you can report them through EDDMapS (Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System). Visit www.eddmaps.org to download the app onto your smartphone.

Spread the word (and not the weeds) in your communities!

The Nevada Nuisance Weed Field Guide. This guide is available to the public

for free and can be picked up at the UNR Extension office located at 4955 Energy Way, Reno.

Photo by Carrie Jensen

Thoughts on My Garden

By Angela White

A hummingbird hovers over a zinnia for a meal of nectar.

Photo by Becky Colwell

My garden is my happy place and my personal haven. It is a private sanctuary that lightens my mood, makes me smile, and feeds my soul.

I love to sit by the huge ponderosa pine in the middle of my yard early in the morning and watch the birds on the feeders. I've become fascinated by avian social hierarchy within and between species. I've seen evening grosbeaks arguing for seating priority, I've watched a redwing blackbird seize a lesser goldfinch by the leg and throw it off the feeder.

And I really wonder how the presence of a solitary red-breasted nuthatch can cause a horde of juncos and chickadees to flee to another tree. Apparently the dominant bird isn't necessarily the biggest or the brightest. It's a mystery to me!

As the morning warms up, pollinators wake up and start to look for breakfast. Seeing bumble bees asleep in flowers, I ask myself: Do they wake up hungry? Is pollen their coffee substitute? After all, I learned from a Zoom class that they have learned preferences and that they really do respond to caffeine.

Some plants can replenish their nectar within minutes. I wonder if those are the ones that have pollinators buzzing incessantly around them.

And then the hummingbirds arrive! What joy to watch these tiny aggressive birds with their beautiful plumage and long grooved tongues. Their flight is mesmerizing; I can practically feel the heat being released by their high metabolism.

I wander around the yard looking at everything and puzzling over why some plants are struggling and others excelling. So often, we gardeners focus on performance rather than pleasure. We dwell on metrics like bloom size and fruit production, rather than intangible benefits, like the way a garden soothes us in a stressful situation or helps us accept the inevitable.

A garden teaches us many things: That it will probably survive without us; that we can fail at a project one year and improve our technique the next. In its leafy surrounds, we can release our (unrelated to the garden) anger with a muttered curse and a hearty whack at recurring weeds. It rewards us with gorgeous flowers, tasty vegetables, and a host of new winged friends who come to share our bounty.

That's my take. I can't wait for the snow to melt so I can welcome the new season. I hope that you feel the same.

A (Not So Secret) Garden for Teaching and Learning

Photos & article by Martha McRae

The Rancho San Rafael community garden, site of the MG demonstration and teaching garden, is in the Farm and Families area, down the hill from the Dinosaur Park.

Tucked away in the Nevada Farms and Families area at Rancho San Rafael Regional Park is an expanding garden aimed at demonstrating gardening techniques and teaching skills to novices and veterans alike.

The area, attended by Washoe County Master Gardener volunteers, adjoins a community garden that was established earlier by the park’s rangers in a pasture that had been used for pony rides when the area was part of the now-closed Great Basin Adventure Park.

The community garden offers 13 raised beds for community members who do not have growing space to grow vegetables, herbs, and flowers for their use. It also includes a row garden where Master Gardener volunteers grow vegetables and herbs for donation to the Reno-Sparks Gospel Mission.

A row garden grows tomatoes, peppers,

and other vegetables for donation to feeding programs.

The Master Gardeners program began developing the teaching and demonstration garden in June 2022, with a humble beginning of just two raised beds. In the spring of 2023, with help from a donation from the Washoe County Leadership Academy, we were able to add six additional raised beds and develop, with the park rangers, a better irrigation system throughout the garden.

Later last year, we introduced monthly garden chats that covered a myriad of gardening topics relevant to local gardeners. We also started a monthly mobile Master Gardener help desk, offering on-site expertise similar to what we provide by phone several days a week from the Reno extension office.

Jill Strawder-Bubala leads a garden talk on putting the garden to bed.

Some of our eight raised beds represent different garden styles and strategies, including one devoted to pollinator-friendly plants and another to kid-friendly veggies. We also demonstrate space-maximizing strategies, such as French Intensive and square-foot planting strategies.

A Square Foot garden demonstration.

In the coming year, we plan to expand our garden talk series and to further develop the row garden area into a small market garden that will produce more consistently throughout the growing season. We also hope to add more demo gardens to pique visitors’ interest, such as gardening in straw bales and containers, and to explore techniques to protect plants and extend the growing season in our difficult climate.

Master Gardeners with a newly installed solarizing

garden cover meant to “cook” germinating weeds before planting.

We welcome park visitors and other plant lovers to stop by and check out all we have to offer to the local gardening community. From the park entrance, we’re just down the hill past the Dinosaur Park. Look for additional information on our 2024 garden talks in this newsletter.

Master Gardener Photos

Garlic chives coming up through leaf mulch.

Photo by Becky Colwell

Pansy blooming on covered south facing deck.

Photo by Becky Colwell

Questions or comments?

Reach out to us!

Help Desk Hours: 10 a.m. - 2 p.m. Tuesdays, Wednesdays & Thursdays

Phone: 775-784-4848

Email: ExtensionWashoeMG@unr.edu

Rachel McClure Master Gardener Coordinator

Phone: 775-336-0274

Email: rmcclure@unr.edu

How to become a Master Gardener

WASHOE COUNTY MASTER GARDENER EVENTS

MASTER GARDENER HELP DESK