Recipes for Institutional Use

This publication provides a brief overview of standardized recipes and how they compare to the common recipe. It also covers recipe modification to meet program guidelines and the needs of special populations.

A recipe is a set of instructions with a list of ingredients used to prepare a particular food, dish or drink. These common types of recipes are found in cookbooks and the internet and are shared among friends. People use recipes to replicate foods they enjoy that they otherwise do not know how to make. However, everyday recipes differ from those used to support the food-service industry ranging from their layout to how ingredient modifications are made.

What is a standardized recipe?

A standardized recipe is a recipe that has been tested, evaluated and adapted for use by a particular food-service operation. Food-service operations are responsible for preparing foods outside of the home and can include hospitals, nursing homes, schools, restaurants and catering services, among many others.

Chefs use standardized recipes to make sure a dish tastes the same each time customers order it. Chefs can also use the standardized recipe as a control tool to ensure the quality of food and the amount of food produced is as planned (Egan, n.d.). This way, food and labor costs can be easily calculated and forecasted. Similar to a regular recipe, a standardized recipe needs to produce a product that is close to identical in quality, taste and yield every time it is made, no matter who follows the directions (Institute of Child Nutrition, 2017). The term “standardized” means that the developed recipe has met the requirements of a specific food-service operation. For instance, a standardized recipe made for a hospital will not be considered a standardized one in a school because they have different requirements. One made for a hospital may not be standardized in another hospital, since their kitchens may be furnished with different cooking equipment.

A standardized recipe may also incorporate Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) into its procedures (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2018). Since most food-service operations make food in large quantities, incorporating HACCP helps ensure that food safety is addressed from the beginning to the end (Egan, n.d.).

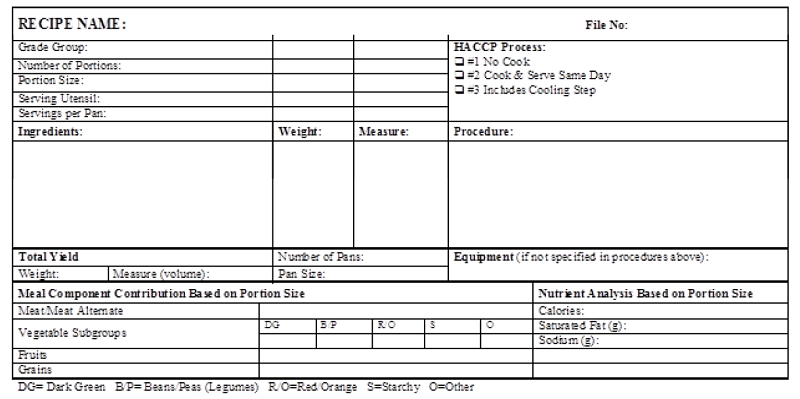

The standardized recipe shares the same key elements of a typical recipe, such as a recipe title, yield, serving size, additional prep, ingredient list, directions and nutritional information. However, it can also have other elements that are tailored for use by the specific food-service operation. Since they usually deal with large quantities of food, the format is laid out in a more systematic and user-friendly way for employees.

Figure 1 shows a sample standardized recipe template for a school food-service operation. The format is different from a regular recipe found in recipe books or on the internet. This standardized recipe template looks more like a chart and has more requirements on measurements and equipment.

What are the advantages of using standardized recipes?

There are many reasons why standardized recipes are used in food-service operations. According to the Institute of Child Nutrition (2017), use of standardized recipes ensures consistent food quality and meets customers’ expectations, whether students in a school or patients in a hospital. It also ensures accurate nutrition content every time when served with the same portion, which is important for schools, hospitals and nursing homes. With predictable yield, the recipe can help prevent food waste and shortages on the serving line. With predictable yield and accurate measurements of ingredients, the standardized recipe helps with planning, purchasing and inventory control. Ingredient quantities can be easily calculated and recorded, and thus purchasing and inventory control are made easier. A standardized recipe may also provide guidance and outline employees’ necessary tasks, so there is little room for mistakes.

Creating recipes that meet program guidelines

Besides making recipes that meet the food-service operation’s needs, recipes also have to meet requirements associated with special programs. For example, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has 15 federally funded food programs designed to end hunger and obesity (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2019). Among these are programs that serve meals and are implemented at the local level.

All federal food program requirements are based on the latest U.S. dietary guidance, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020 – 2025. These guidelines are developed jointly by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and are updated every five years. Their primary purpose is for Americans to make better food choices to improve health and prevent chronic diseases (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2020). These guidelines serve as the foundation for many federal food programs that play a critical role in supporting health and wellness through healthy, nutritious foods.

Some of these federal food programs include the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP), the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and the School Breakfast Program (SBP). Meals provided in these programs must meet the meal pattern standards so that they can be reimbursable (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2013). Thus, recipes used to support these programs should be created to meet those requirements.

For example, a reimbursable child’s lunch needs to include five food components: milk, meat, vegetables, fruits, and grains (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2013). Depending on the age group, a certain amount of each must be met in every food component. Thus, it is important to recognize that meal providers are constrained by programmatic nutrition standards and meal pattern requirements.

Participating food-service providers must plan meals using recipes that will meet these program requirements and be appetizing enough to be consumed. Healthy meals cannot be nutritious unless they are consumed. For more information on guidelines in federal food programs, visit the USDA Food and Nutrition Service website.

Modifying recipes for special populations

Knowing the target audience is vital, as they may have particular needs. Special populations will have different dietary requirements to consider based upon their life stage, medical conditions, cultural and lifestyle choices, food intolerances or allergies, etc. Food-service providers should have the ability to modify recipes to address the needs and concerns by offering alternatives to their patients or consumers.

In hospitals and nursing homes, clients and patients with medical conditions, may need a therapeutic diet to help manage or treat certain medical conditions such as a renal, clear liquid, or carb-controlled diet. Nutrition professionals such as registered dietitians have carefully analyzed meals served under these dietary orders to ensure they meet their patients’ nutritional requirements and do no harm.

Chefs should be mindful of food allergens and their ability to cross-contaminate other foods. Consumption or exposure to these food allergens may create a life-threatening situation for people who are allergic to them. While there are over 160 known food allergens, the eight most common ones responsible for over 90% of allergic reactions are: milk, egg, wheat, soy, peanuts, fish, crustacean shellfish and tree nuts (Southern Nevada Health District, 2019). A facility menu should be cross-referenced with an allergen guide listing all menu items containing ingredients from the eight most common food allergens. This will help facility staff and consumers determine if a menu item should be avoided.

Chefs should be mindful of food allergens and their ability to cross-contaminate other foods. Consumption or exposure to these food allergens may create a life-threatening situation for people who are allergic to them. While there are over 160 known food allergens, the eight most common ones responsible for over 90% of allergic reactions are: milk, egg, wheat, soy, peanuts, fish, crustacean shellfish and tree nuts (Southern Nevada Health District, 2019). A facility menu should be cross-referenced with an allergen guide listing all menu items containing ingredients from the eight most common food allergens. This will help facility staff and consumers determine if a menu item should be avoided.

Food and medication interactions can be another concern that chefs should be mindful of when considering substitutions for existing recipes. For example, people who take Warfarin or blood thinners need to maintain a consistent daily consumption of vitamin K. It should not vary widely from day-to-day as this variance can decrease the effect of Warfarin, a commonly prescribed blood thinner (University of Michigan Medicine, n.d.). Another example is how grapefruit interacts with some statins, which are drugs that lower cholesterol. The grapefruit contains a chemical that may cause the medication to stay in the body longer and then cause damage to the liver and kidneys (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2017). Therefore, a nutrition professional, such as a registered dietitian. should review modifications to recipes used in institutional settings for foods given to patients under therapeutic diet orders.

Food and medication interactions can be another concern that chefs should be mindful of when considering substitutions for existing recipes. For example, people who take Warfarin or blood thinners need to maintain a consistent daily consumption of vitamin K. It should not vary widely from day-to-day as this variance can decrease the effect of Warfarin, a commonly prescribed blood thinner (University of Michigan Medicine, n.d.). Another example is how grapefruit interacts with some statins, which are drugs that lower cholesterol. The grapefruit contains a chemical that may cause the medication to stay in the body longer and then cause damage to the liver and kidneys (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2017). Therefore, a nutrition professional, such as a registered dietitian. should review modifications to recipes used in institutional settings for foods given to patients under therapeutic diet orders.

When developing recipes, one should be mindful of the culture, religions, and beliefs of others. For example, one aspect of observing kosher is to separate meat and dairy. Therefore, a facility that serves kosher food needs to modify its recipes and kitchen layout accordingly.

And finally, pregnant women, young children and older adults (among others) are considered at-risk groups because of their potentially vulnerable immune systems. When developing recipes for these groups, it is necessary to avoid undercooked meat and seafood, deli meats, unpasteurized milk and cheese, and even vegetables that are not thoroughly washed. Being careless about certain ingredients can cause foodborne illnesses leading to severe consequences As many additional considerations and scenarios exist, it is recommended to consult with a registered dietitian to modify a recipe to meet the needs of special populations.

Conclusion

In summary, standardized recipes differ from common ones because they have been tested, evaluated, and adapted for a particular food-service operation. They help food-service providers control the quality of food, along with costs. The testing and evaluation for standardized recipes help culinary professionals decide whether an item should be included on a menu. Standardized recipes are also valuable for tracking requirements needed to meet federal guidelines or those populations with special needs or allergies. A nutrition professional, such as a registered dietitian, can help food-service operations ensure their recipes meet dietary needs and program requirements.

References

- Egan, B. (n.d.). Chapter 6 – Standardized Recipes – Introduction to Food Production and Service. Pressbooks. Retrieved August 10, 2020,

- Institute of Child Nutrition. (2017). Why Use Standardized Recipes [Fact sheet]. Retrieved August 10, 2020, f

- Southern Nevada Health District. (2019). Allergy Aware: What’s Hiding in Your Menu? Allergen Guide. Food Allergy Awareness Materials. Retrieved October 28, 2021

- University of Michigan Medicine. (n.d.). Warfarin and Vitamin K. Michigan Medicine. Retrieved August 10, 2020,

- US Department of Agriculture. (n.d.). Food and Nutrition Service Nutrition Programs. Retrieved August 10, 2020,

- US Department of Agriculture. (2019, July 1). About FNS. Retrieved August 17, 2021

- US Department of Agriculture. (2013). Nutrition Standards for CACFP Meals and Snacks [Fact sheet]. Retrieved August 10, 2020

- US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture. (2020, December). Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020 – 2025. Ninth Edition. Retrieved August 17, 2021,

- US Food and Drug Administration. (2017, July 18). Grapefruit Juice and Some Drugs Don’t Mix. Retrieved August 10, 2020,

- US Food and Drug Administration. (2018, January 29). Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP). Retrieved August 10, 2020,

- Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. (2020, February 21). Recipe Template for one grade group/portion size. Standardized Recipes. Retrieved August 10, 2020,

Buffington, A., and Li, S.

2021,

All About Recipes Part II,

Extension | University of Nevada, Reno