Introduction

Rainwater harvesting is the practice of collecting and storing runoff from rooftops for later use on lawns, gardens and other landscaping. Rainwater harvesting is an ancient concept, and has been practiced for thousands of years in Asia, India and the Middle East as a way to supplement water supplies during dry periods.

Before municipal water systems existed, people often relied on rainwater to supplement drinking and irrigation water drawn from rivers or wells.

With the growth of urban centers complete with municipal water and storm drain systems, many of us have forgotten what people knew long ago: rainwater is a high-quality, free source of water that can be used for irrigation with minimal effort. The water is soft, low in salts and dissolved minerals and excellent for leaching desert soils.

Residential rain barrel. Image by Connecticut NEMO Program.

What can rainwater be used for?

Harvested rainwater can be used for pet and livestock watering, car washing, and sometimes even to supplement nonpotable water uses, such as toilet flushing and evaporative cooling systems. Rainwater should never be used for drinking water purposes unless it has been purified. Because harvested rainwater is not potable, it must be managed to protect both household occupants and the municipal water system from contamination. If used for a purpose such as toilet flushing, proper cross-connection protection, system maintenance and system marking are essential to protect household occupants and prevent contamination of the municipal water system.

While precipitation in the West is generally of good quality, rainfall is infrequent enough that pollutants may have collected on roofs. The first flush of rain may contain dust, debris, bird or other animal droppings. To eliminate these substances, many commercial rainwater collection systems have devices that divert the first few gallons of runoff onto the ground.

Benefits of Rainwater Harvesting

- SAVES you money by using “free” water

- REDUCES the use of treated drinking water for landscape irrigation

- IMPROVES plant health by irrigating with high quality, salt-free rainwater

- REDUCES the potential for moisture damage around your home’s foundation

- KEEPS water out of the municipal storm drain system

- REDUCES dependence on groundwater supplies

- DECREASES polluted runoff to rivers and creeks

- REDUCES flood flows

Stormwater yields from various surfaces

| Surface |

Percent Yield |

| Roof |

90-95 |

| Paving |

90-100 |

| Gravel |

25-70 |

| Soil, bare and flat |

20-75 |

| Soil, with vegetation |

10-60 |

| Flat lawn, sandy |

5-10 |

| Flat lawn, clayey |

13-17 |

Source: Harvesting Rainwater for Landscape Use, University of Arizona

Maintaining your system

Regular maintenance is essential to keep your rainwater harvesting system working correctly. Follow these maintenance tips:

- Keep rain barrels and cisterns free of debris.

- Control and prevent erosion near the overflow outlet.

- Keep gutters and downspouts free of debris.

- Install gutter guards to keep out leaves and other large objects.

- Periodically flush debris from rain barrels and cisterns and decontaminate with bleach.

- Clean and maintain filters.

- Repair leaks promptly.

- Expand berms around landscaping as plants grow.

- Monitor irrigation systems and plant water needs and adjust as needed to maintain a healthy landscape.

Amount of roof water that can be harvested based on annual precipitation

| Inches of Rain |

Gallons per square foot |

Gallons per 1,000 square foot roof |

Gallons per 2,000 square foot roof |

| 7 |

4.4 |

4,400 |

8,800 |

| 9 |

5.6 |

5,600 |

11,200 |

| 11 |

6.8 |

6,800 |

13,600 |

Planning a rainwater harvest system

To determine whether rainwater harvesting will work for you, visualize your property. Where does the water from your roof go when it rains? If you’re not sure, observe it during the next rainstorm. It’s likely that much of the water travels via gutters and downspouts onto paved surfaces and into the storm drain system rather than soaking into the ground. When this occurs, stormwater often picks up pollutants deposited on surfaces, such as oil drips, lawn fertilizer and road salts, and carries them into our surface water bodies, contributing to water pollution.

Rainwater harvesting does not need to be complicated. For example, if your roof has a gutter system, there are a variety of low-cost products available that can be attached to the downspouts to divert the water to your plants. First, determine which areas of your landscape will benefit from additional water. Then determine whether berms should be installed to help retain the water. The existing soils may need to be amended to allow the water to soak into the ground reasonably quickly. Sandy soils infiltrate well, but clay-rich soils have slow infiltration rates and may need amendments such as compost to enhance drainage. See LID in Northern Nevada: Soil Considerations, University of Nevada Cooperative Extension FS-09-23, for more information.

To help plan your rainwater harvesting system, draw a simple map of your property. The map should identify the location of your house or other buildings, sidewalks and other surfaces that will carry water. This is often referred to as the “catchment,” or the area from which runoff is collected. Use arrows to indicate the direction in which water flows across each surface. Show landscaped areas and types of vegetation by their general water needs. The plan will help you decide where and how to direct rainwater, or where to store water should you decide storage is possible.

Should I store rainwater?

In an average year, the Reno area receives about 7.5 inches of precipitation. For a house with a roof area of about 1,500 square feet, if about 90 percent of the water makes it to a storage tank, approximately 6,300 gallons of water could be collected. While this is not enough to supply all our summer irrigation needs, the water could be used to irrigate potted plants or plants that need a bit of extra water.

However, much of our precipitation arrives during the winter months, when the need for landscape irrigation is minimal. Storage is most useful when the water is available at the time of greatest need. In northern Nevada, this occurs during the summer months. However, we do often receive significant amounts of precipitation in the form of summer thunderstorms or spring rains, so a storage system may make sense for you if it fits into your overall goals and needs.

If you do decide to capture and store rainwater, it is important to know how much water will be delivered to your storage tank at one time. Perhaps you are only collecting water from one side of your 1,500-square foot roof. When we receive a 1-inch rainfall, 750-square-feet of roof will provide about 420 gallons of water. However, small barrels generally only hold about 55 gallons. Be sure to include an overflow mechanism and a plan for the excess water when using them. It’s also a good idea to install a ”Roof Washer” or “First Flush” component. These commercially available devices trap or divert the first few gallons of runoff from the roof and channel the dirty water away from the barrel or cistern. Plan to divert about 10 gallons per 100 square feet of roof area.

This cistern collects water from the roof of the restroom facility. The water can be used to flush the toilets. Image by Susan Donaldson.

Storage Volume

Use the following equation to calculate the volume of water in gallons expected from a specific size roof:

V = A x R x 0.90 x 7.5 gallons/ft3 where:

V = volume expected from specific size of roof

A = the surface area of the roof, in square feet

R = rainfall depth, in feet (convert inches to feet by dividing by 12)

0.90 = a factor to allow for losses to evaporation, etc.

7.5 = a factor to convert cubic feet to gallons

This will help you choose the correct volume for the rain barrel.

For a description of various Low Impact Development practices

consult the following Fact Sheets in the “Low Impact Development in Northern Nevada” series:

- LID: An Introduction, FS-09-22

- Soil Considerations, FS-09-23

- Rainwater Harvesting, FS-09-24

- Bioretention, FS-09-25

- Vegetated Swales and Buffers, FS-09-26

- Green Roofs, FS-09-27

- Plant Materials, FS-09-28

- Porous Pavement, FS-09-29

- Roadway and Parking Lot Design, FS-09-30

- Maintenance, FS-09-31

Rain barrels

There are many commercial barrels available. A quick search of the Internet will reveal a wide variety of shapes, sizes and appearances. You can also construct your own rain barrel using a 55-gallon plastic drum. Make a hole at the top of the barrel for the gutter downspout and place a screen over it to exclude debris and insects. Next, install a spigot to which a hose can be attached. Place the spigot a few inches above the bottom of the barrel so that any debris will remain at the bottom of the barrel until you clean out the tank. Barrels that are open to the atmosphere can become breeding grounds for mosquitoes, and should be avoided. Make sure to seal the lid and any gaps connecting the gutter downspout to the lid. It’s also important to have a tamper-proof design that won’t attract curious children.

Since the water will flow from the barrel under the force of gravity, place it on cinder blocks or a platform elevated at least 15 inches above the ground. If you would like to capture more rainwater, consider linking two or more barrels together, or placing a barrel at each downspout from your roof. Always design an overflow pipe to allow excess water to safely flow away from the house without causing erosion.

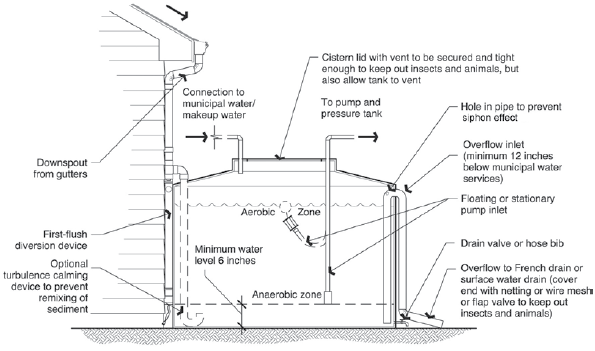

Cisterns

Cisterns are water tanks used to collect and store larger volumes of rainwater, usually from roofs. In the past, they were commonly used to supplement water supplies in areas where rainfall was infrequent. Some communities around the world still rely on them as a source of water. Check with your county for any regulations or restrictions on the use of cisterns.

The tank volume depends on roof collection area, the amount of rainfall to be stored, the space available, etc. Some types of roofs are not suitable for water collection, including roofs treated with tar or similar substances. Appropriate materials include tile, concrete or slate shingles, aluminum or plastic.

Cisterns can be made of plastic, metal or concrete. They must be watertight, have smooth interior surfaces and be large enough to capture the desired amount of water. Locate cisterns aboveground or underground, in crawl spaces or other locations. If cisterns are placed below-grade, a pump or other mechanism will be needed to withdraw water. Do not place cisterns near sewage lines or other sources of contamination, and be sure to slope the ground surface away from the cistern to allow adequate drainage. Ground settling can cause cracks in cisterns, so locate them on firm ground away from tree roots. A full cistern can be very heavy, since each gallon of water weighs 8.3 pounds. Remember that aboveground cisterns can be subject to freezing, so winter freeze protection such as insulation or heat tape may be needed.

When determining size, allow for water that will be lost to leaks, evaporate from the roof or be blown away by wind as well as the volume that is diverted by a roof-washing fixture. Some estimates assume a one-tenth to one-third loss. Include an access point to allow for cleaning. The cover should be watertight and locked to avoid contamination or accidents. Screen inlets and outlets to keep mosquitoes and other vermin out of the tank. Include an overflow drain and route the excess water away from buildings and onto areas where the water can soak into the ground.

Regular maintenance is required to keep the water clean. Inspect cisterns regularly and periodically empty and clean them with a dilute chlorine solution consisting of one-fourth cup of 5.25 percent unscented bleach in 10 gallons of water. Flush the tank thoroughly before using it again to remove sediment and chlorine residues.

Elements of a cistern used for water harvesting. Image by Forgotten Rain, LLC.

For additional detailed planning and design information

refer to the latest versions of the Truckee Meadows Low Impact Development Handbook and the Truckee Meadows Structural Controls Design Manual available at www.tmstormwater.com.

Additional information about rainwater harvesting can be found at:

- Forgotten Rain, Rediscovering Rainwater Harvesting, www.forgottenrain.com

- Harvesting Rainwater for Landscape Use by Patricia Waterfall, http://ag.arizona. edu/pubs/water/az1052/

- Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond by Brad Lancaster, www. harvestingrainwater.com/

Technical review provided by Chris Conway, Certified Professional in Sediment and Erosion Control.

Donaldson, S.

2009,

Low Impact Development in Northern Nevada: Rainwater Harvesting,

Extension | University of Nevada, Reno, FS-09-24