Introduction

If you have any involvement with federal public lands, you probably have been invited to become involved in a National Environmental Policy Act1 (NEPA) process. When NEPA was first enacted, it required federal agencies that propose “major federal actions” (federal actions that could have environmental effects) to enter into a public process and seek comments and input from interested citizens. NEPA was intended to analyze only major projects or actions. The Council on Environmental Quality defines major federal actions to include adoption of official policy (that is, rules and regulations), adoption of formal plans, adoption of programs, and the approval of specific projects. The judicial system, through various rulings, also has shaped how management agencies apply and implement NEPA. Collectively, this makes it much more difficult and critical for people to be vigilant and respond to proposed actions that may directly affect their activities.

This publication is designed to help Nevada residents understand NEPAhow agencies apply and implement NEPA analysis, and how and why interested citizens should respond. A companion publication (SP 09-15), provides guidelines for NEPA response.

History

Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act in December, 1969 and President Richard Nixon signed it into law on Jan. 1, 1970. NEPA is often called the “Magna Carta” of environmental laws. It established U.S. national policy toward the environment and created the President's Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ).

With some limited exceptions, all federal agencies in the executive branch must comply with NEPA before they make final decisions about federal actions that could have significant environmental effects. Thus, NEPA applies to a wide range of federal actions that include, but are not limited to: federal construction projects; plans to manage and develop federally owned lands; and federal approval of non federal activities, such as grants, licenses and permits. NEPA does not apply to the President, to Congress or the federal courts. The law is applied to any federal, state or local project that uses federal funding or involves work performed by the federal government.

Purpose of NEPA

The stated purpose of NEPA is:

"To declare a national policy which will encourage productive and enjoyable harmony between man and his environment; to promote efforts which will prevent or eliminate damage to the environment and biosphere and stimulate the health and welfare of man; to enrich the understanding of the ecological systems and natural resources important to the Nation..."

An original intent of NEPA was to put environmental concerns on par with economic motivations and technological feasibility when making decisions that affect the environment. These concerns may be hydrological, geological, biological, ecological, social, and/or health related. More recently, archeological, historical, cultural, visual and financial - management concerns have been added to the NEPA process.

NEPA allows all citizens to work with the agencies so that all pertinent information is available to the decision makers. Two significant desired outcomes of the environmental review process are increased citizen involvement and management decisions based upon all available information. If both outcomes are achieved, the desired effect is implementation of management actions that best meet the agencies stated goals and objectives, with a lower probability of unintended consequences to all affected interests.

The evolution of NEPA

The total number of Environmental Impact Statements2 (EIS’s) filed by all federal agencies has decreased significantly from 5,834 during the period of 1970-72, to 557 in 2007 (NEPA net). This is most likely a function of agencies learning the process. During the 10 year period from 1998 to 2008, the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) filed 1,466 NEPA applications, and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) filed 428 EIS’s. Statistics derived from NEPAnet indicate that BLM is challenged more often through litigation than the USFS. From 2001 to 2007, of the 1030 total EIS’s filed by USFS, 33 percent (342) were litigated vs. 45 percent (112) of the 274 BLM EIS’s. However, only 31 percent (35) of the BLM EIS litigations resulted in an injunction or remand, vs. 40 percent (137) of the USFS cases.

Even though the total volume of NEPA processes appears to have stabilized for the BLM and USFS, the content, scope and volume of NEPA documents have expanded in size since 1970. EIS documents were initially expected to be 75 pages or less and Environmental Assessments3 (EA’s) 15 pages or less. According to agency staff, both BLM and USFS NEPA documents typically exceed these initial expectations.

What NEPA does and does not do

NEPA establishes a public, interdisciplinary framework for federal decision-making to ensure that agencies consider social and environmental factors when they propose and analyze their actions.

NEPA requires federal agencies to consider the environmental effects of their actions and be informed about the environmental consequences of their decisions

NEPA does not:

- mandate protection of the environment

- require the decision-maker to select the environmentally preferable alternative

- prohibit actions that may result in adverse environmental effects

Federal agencies usually must address many concerns and follow the guidelines of multiple policies. By nature, final decisions are often a compromise that best integrates and addresses conflicting concerns and policies.

NEPA oversight

Three federal agencies have specific oversight responsibilities for NEPA: the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ); Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Office of Federal Activities; and the U.S. Institute for Environmental Conflict Resolution.

Primary responsibility is vested in the CEQ. Its responsibilities are to:

- ensure that federal agencies meet their obligations under the Act

- oversee implementation of NEPA, principally through issuance and interpretation of NEPA regulations that implement the procedural requirements of NEPA

- review and approve federal agency NEPA procedures, approve alternative arrangements for compliance with NEPA in the case of emergencies, and help resolve disputes between federal agencies and other governmental entities and members of the public.

The EPA’s Office of Federal Activities reviews federal environmental impact statements and some environmental assessments. It provides comments for the public via publication of summaries (of the documents) in the Federal Register. EPA’s reviews are intended to assist federal agencies to improve their NEPA analyses and decisions.

The U.S. Institute for Environmental Conflict Resolution was established by the Environmental Policy and Conflict Resolution Act of 1998. Its mission is to help resolve conflict about environmental issues that involve federal agencies. The Institute is part of the federal government and is located within the Morris K. Udall Foundation, a federal agency located in Tucson, Ariz. It is designed to be an independent and neutral organization that helps federal agencies work with citizens; state, local, and tribal governments; private organizations; and businesses to reach common ground. The Institute provides dispute resolution as an alternative to litigation and other adversarial approaches. The Institute also is charged with assisting the federal government in the implementation of the substantive policies set forth in Section 101 of NEPA.

The NEPA process

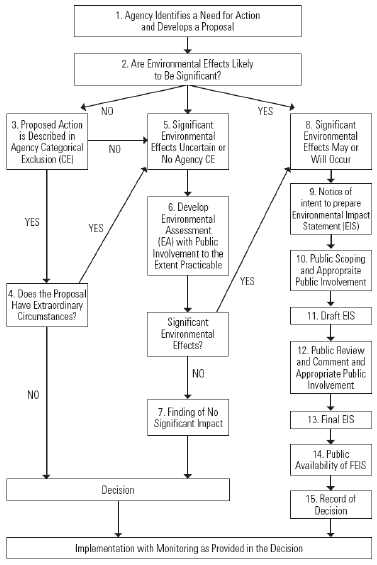

The NEPA process begins when a federal agency identifies an issue that will require a management action. The need for the action may be selfidentified by the agency, or it may be in response to a proposal brought forward by an outside entity. For example, either an individual or commercial interest may apply for a permit to use an area or resource for their benefit. Based upon the need, the agency develops a proposal for action (Figure 14, Box 1). If the receiving agency is the only federal agency involved, it will automatically be the “lead agency.” As the lead agency, it has the primary responsibility for compliance with NEPA.

The flowchart in Figure 1 is from the CEQ’s Citizen’s Guide to NEPA. It details the steps of the NEPA process. While agencies may differ slightly in how they comply with NEPA, understanding the basics provides the information you need to work effectively with any agency that proposes federal actions.

Some large or complex proposals involve multiple federal agencies, and/or state, local or tribal jurisdictions. If another federal, state, local or tribal entity has a major role in the proposed action, and also has NEPA or NEPA-like responsibilities under a similar law, that agency may become a “joint lead agency.” A “joint lead agency” shares the lead agency’s responsibility for management of the NEPA process, including public involvement and the preparation of supporting documents.

Other federal, state, tribal or local government agencies may reach a separate conclusion or provide special expertise regarding a proposed action. Their role, however, is smaller than the lead agency. In these situations, the secondary federal, state, tribal or local government agency is a “cooperating agency.” A “cooperating agency” has jurisdiction by law or special expertise with respect to any environmental impact from a proposed or alternative action. Thus, a “cooperating agency” typically has some analytical responsibility related to either its jurisdiction or special expertise. The lead agency, however, is not bound to make decisions desired by the supporting agency. In fact, the lead agency can, and often does, make a decision contrary to the desires of cooperating agency. NEPA requires cooperating agencies be involved in the process and provide input. NEPA also requires the lead agency to coordinate to achieve consistency with the policies and plans of the local government to “the maximum extent possible” (40 CFR 1501.6(a) (CEQ)). Further, the lead agency is bound to achieve consistency, if possible, and document in the EIS acknowledgement where consistency could not be reached (40 CFR 1502.16 (CEQ)).

Once an agency initiates an action, it starts a preliminary analytical approach (Figure 1, Box 2). This step helps determine whether the agency will pursue the path of a Categorical Exclusion (CE), an EA, or an EIS.

Categorical Exclusion (CE) (Figure 1, Box 3)

A CE is a category of actions that the agency has determined does not individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on the quality of the human environment. If an agency determines the action falls under a CE, the procedures used by the drafting agency are published in the Federal Register. As with all draft NEPA documents, public comments are solicited. Participation in this comment period is an important way to be involved in the development of a particular CE.

Environmental Assessments (EA) (Figure 1, Box 6)

The purpose of an EA is two-fold: 1) to determine whether the potential environmental effects of a proposed action warrant preparation of an EIS; and 2) for the agency to look at alternative means to achieve its management objectives. The EA is intended to be a concise document that:

- briefly provides sufficient evidence and analysis for determining if preparation of an EIS is necessary

- aids an agency’s compliance with NEPA when no EIS is necessary

- facilitates preparation of an EIS when one is necessary

An EA should include brief discussions of:

- the need for the proposal, and alternative courses of action for any proposal which involves unresolved conflicts concerning alternative uses of available resources

- the environmental impacts of the proposed and alternative actions

- a listing of agencies and persons consulted

An EA serves to evaluate the significance of a proposal for agency actions. It should focus on the context and intensity of the effects that may “significantly” affect the quality of the human environment. Often the EA will identify ways in which the agency can revise the action to minimize adverse effects. When preparing an EA, the agency has discretion for the level of public involvement (Figure 1, Box 6). CEQ regulations state that the agency shall involve environmental agencies, applicants and the public “to the extent practicable.” Sometimes agencies will choose to mirror the scoping and public comment periods that are found in the EIS process. In other situations, agencies make the draft EA and a draft Finding Of No Significant Impact (FONSI) available to interested members of the public.

The Environmental Assessment process concludes with either a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) (Figure 1, Box 7) or a determination that preparation of an EIS is necessary. A FONSI document includes statements about why the agency concluded its actions will not have a significant environmental impact. The EA is either summarized in the FONSI or attached to it. There are two circumstances that require agencies to make the proposed FONSI available for public review and comment for 30 days:

- If the type of proposed action hasn’t been previously implemented by the sponsoring agency

- The action is something that typically would require an EIS under the sponsoring agency’s NEPA procedures

For each situation, the FONSI is usually published in the Federal Register, and the notice of availability of the FONSI states how and where the public may provide comments. If the requirement for a 30-day review is not triggered, often the FONSI will not be published in the Federal Register. Rather, it may be posted on the agency’s Web site, published in local newspapers or made available by some other manner. If you have an interest in a particular decision that requires preparation of an EA, you should contact the agency to determine how it will make the FONSI available.

Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) (Figure 1, Box 8)

The most involved level of NEPA analysis is the EIS. A federal agency may choose to initiate the NEPAprocess with an EIS and bypass an EA. An EIS must include descriptions of:

- The affected environment

- The environmental impacts of the “proposed and alternative actions”

- Alternatives of the proposed action, including continuation of the existing action (called the no action alternative)

- Any unavoidable adverse environmental impacts

- The relationship between short term uses of the environment and maintenance of long term ecological productivity, irreversible and irretrievable commitments of resources

- The secondary (indirect) and cumulative effects of implementing the proposed action

A federal agency must prepare an EIS if it is proposing a major federal action that may significantly affect the quality of the human environment. The regulatory requirements for an EIS are more detailed than the requirements for an EA or a CE and are explained below.

Figure 1

*Significant new circumstances or information relevant to environmental concerns or substantial changes in the proposed action that are relevant to environmental concerns may necessitate preparation of a supplemental EIS following either the draft or final EIS or the Record of Decision (CEQ NEPA Regulations, 40 C.F.R § 1502.9(c)).

Notice of Intent and Scoping

The EIS process begins with publication of a Notice of Intent (NOI), stating the agency’s intent to prepare an EIS for a particular proposal. (Figure 1, Box 9). The NOI is published in the Federal Register, and provides basic information about the proposed action in preparation for the scoping process (Figure 1, Box 10). The Notice of Intent provides a brief description of the proposed action and possible alternatives. It describes the agency’s proposed scoping process, including any meetings and how the public can become involved. The NOI also provides an agency point of contact who can answer questions about the proposed action and the NEPA process. The best time to identify issues, determine points of contact, establish project schedules and provide recommendations to the agency is during the scoping period. This period provides the most opportunity to alter existing alternatives, propose new alternatives and refine the proposal. Also, the scoping period usually is the best time to initiate collaborative processes. The overall goal is to define the scope and context of the issues that will be analyzed in depth in the EIS. Specifically, the scoping process will:

- Identify individuals or organizations interested in the proposed action

- Identify the significant issues to be analyzed in the EIS

- Identify and eliminate from detailed review those issues that will not be significant or which have been adequately covered in prior environmental review

- Determine the roles and responsibilities of lead and cooperating agencies

- Identify any related EAs or EIS’s

- Identify gaps in data and informational needs

- Set time limits for the process and page limits for the EIS

- Identify other environmental review and consultation requirements so they can be integrated with the EIS

- Indicate the relationship between the development of the environmental analysis and the agency’s tentative decision-making schedule

Agencies are required to identify and invite the participation of interested persons. The agency should use communication methods best suited for the effective involvement of local, regional and/or national communities which are interested in the proposed action. Video conferencing, public meetings, conference calls, formal hearings or informal workshops are common ways to conduct scoping. Each affected interest should become involved as soon as the EIS process begins and should use the scoping opportunity to make thoughtful, rational presentations about impacts and alternative solutions to potential issues, problems and actions. Some of the most constructive and beneficial interactions between the public and an agency occur when citizens identify or develop clear and reasonable alternative actions that can be evaluated in the EIS. Collaborative processes can improve communication, reduce conflict and provide generally more acceptable and practical alternatives and solutions.

Draft and Final EIS

Upon completion of the NOI and public scoping processes, the agency will prepare a draft EIS which is released for public comment. The shortest allowable public comment period is 45 days, which can be extended at the discretion of the lead agency. If the draft document is large and complex it is common to request an extended period for public comment. Comments on the document and proposed action may be received in response to a scoping notice or in response to public review of an EA and FONSI or draft EIS. Comments received at other times in the process may not require a formal response. However, all substantive comments received before reaching a decision must be considered to the extent feasible (40 CFR 1503.4) (BLM NEPA H-1790-1). Normally agency responses to substantive comments should result in changes in the text of the EA or EIS. Additionally, BLM NEPA Handbook H-1790-1 recommends that if the comments warrant further consideration, the decision-maker must determine whether the new impacts, new alternatives, or new mitigation measures must be analyzed in either the final EIS or a supplemental draft EIS. Following public review and comment upon the draft EIS, the lead agency prepares a final EIS unless a decision is made to terminate the EIS. Once the final EIS is prepared, it is printed, filed with the EPA, and distributed to the public. Public notification of the availability of the final EIS must include publication of a notice of availability (NOA) in the Federal Register for actions with effects of national concern. The date the EPA notice appears in the Federal Register initiates the required minimum 30-day availability period. This is not a formal public comment period. Agencies may receive comments but response to them is discretionary.

Any comments received at this time may be addressed in the Record Of Decision (ROD). The decision-maker must determine if the comments have merit. That is, do they identify significant new circumstances or information relevant to environmental concerns and bear upon the proposed action. If so, the decisionmaker must determine whether minor changes can be made to the existing EIS or to write a supplement to the final EIS.

The Record of Decision (ROD)

A written ROD documents the selected alternative and any accompanying mitigation measures. The ROD must be signed by the decision-maker. Except as described below, the ROD cannot be issued until the latter of the following dates:

- 90 days after the publication of the EPA’s notice of filing of the draft EIS

- 30 days after publication of the EPA’s notice of filing of the final EIS

The lead agency must notify the public about the availability of the ROD, and notification must include publication of a notice of availability (NOA) in the Federal Register for actions with effects of national concern. If the agency’s decision is subject to 30-day appeal to the Interior Board of Land Appeals (IBLA), then the ROD may be issued at the same time the final EIS is filed. This allows both 30-day periods to run concurrently. If the ROD is issued at the same time as the final EIS, the EIS must identify and explain the appeal provisions. If the ROD is issued in full force and effect, then it cannot be issued until 30 days after publication of the EPA’s notice of filing the final EIS.

Why you should become involved in a NEPA process

NEPA’s environmental review process provides citizens an opportunity to become involved in the federal agency decision-making process. Active participation has several potential benefits:

- increase your understanding of a federal agency’s proposed action

- increase your opportunity to provide thoughtful alternatives (via comments) to achieve the agency’s goals and objectives

- reduce the unintended consequences of a proposed federal action and preserve appeal rights. If you do not have standing by participating you cannot appeal in any venue

- must be involved to have legal standing. To obtain legal standing you must provide comments early in the NEPA process and continue active involvement

Additional opportunities for development of proposed actions and/or alternatives can be employed by either the federal agency or suggested by participants. Coordinated Resource Management (CRM), Resource Advisory Council subgroups and the Creeks & Communities strategy employed by national and state Riparian Service Teams are examples of social processes that provide opportunities to reduce conflict, increase awareness and add value to the NEPA process.

You should become involved if the:

- Proposed federal actions affect you directly

- Proposed federal actions affect your livelihood directly

- Proposed action is/is not environmentally sound

- Proposed action is/is not practicable

When you should become involved in a NEPA process

- The earlier in the process the better. Ideally, it is best to get involved early in the scoping process

- Any time after scoping when you become aware that the action affects you

What to expect from being involved

You can make a difference!

The CEQ maintains a Web site that is very useful for NEPA information and guidance.

See Part Two - NEPA Response: A Guide for Reading and Responding to NEPA Documents for suggestions on how to analyze and effectively respond to specific NEPA documents.

Further References

- NEPA Response: A Guide for Reading and Responding to NEPA Documents Part Two of a Two Part Series fact sheet

- A Desk Guide to Cooperating Agency Relationships 2005 BLM.

- BLM Land Use Planning Manual MS- 1601 BLM.

- BLM National Environmental Policy Act H-1790-1 BLM.

- CEQ NEPA Citizens Guide 722 Jackson Place, NW Washington, DC 20503 White House

- NEPAnethttp://www.nepa.gov/nepa/nepanet.htm

- National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §§ 4321- 4347.

1National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §§ 4321-4347.

2An environmental impact statement (EIS) is prepared when the lead agency has determined a proposal is likely to result in significant adverse environmental impacts.

3The purpose of an EA is to determine the significance of the environmental effects and to look at alternative means to achieve the agency’s objectives.

4Only those boxes that are critical to affected interests, their involvement and response to NEPA documents are addressed in this Fact Sheet.

McCuin, G. Schultz, B., and Orr, R.

2009,

Know NEPA: Important Points for Public Participation Part One of a Two-Part Series,

Extension | University of Nevada, Reno, FS-09-14