Introduction

Spotted knapweed, a member of the sunflower (Asteraceae) family, is a noxious weed in Nevada. It is thought to have been introduced into the United States from Eurasia as a contaminant in alfalfa seed. Long before it was considered to be a serious weed, it was spread in domestic hay and by man’s activities. Spotted knapweed is now invading rangeland throughout Canada and the western United States, including Nevada.

Identification

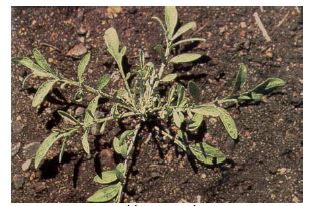

Spotted knapweed (Cenaurea maculosa) is a biennial or short-lived perennial with a deep taproot. The taproot forms a new shoot each year. Early in the season, the plant appears as a rosette, a leafy prostrate plant (Fig. 1). Its rosette leaves develop on short stalks at the base of the plant. They are grayish green and deeply divided into oblong lobes.

Figure 1. Spotted knapweed rosettes appear in early spring.

Spotted knapweed usually grows two to four feet tall and then flowers. The slender stems are upright, branched, and hairy (Fig. 2). The stem growth occurs mostly in June, and the majority of the branching is on the upper half of the plant. Stems growing on upland sites will not be as tall as those on sites with higher moisture.

Figure 2. Spotted knapweed has erect stems with branches.

Spotted knapweed’s alternate, stalkless (sessile) leaves are pale grayish green and one to three inches long. The lower leaves have a rough exterior and distinctive leaf margins that are indented or divided about halfway to the midrib (vein in the center of the leaf). The small, upper leaves are simple and more linear.

Spotted knapweed flowers bloom singly at the ends of branches from late June through August. The purple to pink flowers resemble those of thistles (Fig. 3). Each flower head has stiff bracts surrounding its base. The fine, vertical veins and dark, comb-like margins at their tips give the bracts a spotted appearance.

The oval, brown to black seeds are about ⅛ inch long with a tuft of bristles at the tip. On average, there are about 1,000 seeds produced per plant, but up to 25,000 seeds can be generated on a large plant.

Figure 3. Spotted knapweed’s pinkish purple flowers have bracts with dark spots.

Habitat

Spotted knapweed is invading rangeland throughout the western United States. In Nevada, there are records of this weed in White Pine, Lincoln, Washoe, Elko, and Nye counties. It invades open and disturbed areas such as dry meadows, pastureland, stony hills, old fields, roadsides, and the sandy or gravelly floodplains of streams and rivers. Spotted knapweed infestations often occur along with diffuse knapweed.

This weed can tolerate most of the dry conditions found in Nevada, but can survive in high-moisture environments as well. It prefers to grow in well-drained soils, but infests soils of all types. Spotted knapweed does not tolerate shade well. Its early spring growth makes spotted knapweed a tough competitor for soil moisture and nutrients to plants that germinate later.

Impact

In 1997, spotted knapweed was found in 14 western states. It is observed that the more soil disturbance there is, the higher the density of a spotted knapweed stand. This weed rapidly colonizes disturbed areas, but is also capable of infesting well-managed rangelands. Spotted knapweed reduces biodiversity by choking out native vegetation. It can readily occupy over 95 percent of the available plant community. Spotted knapweed plants growing along streams increase erosion and damage aquatic life.

Spotted knapweed reproduces by seed, which can remain viable in the soil for many years. When the mature flower dries out, the bracts open exposing the seeds. They can then be flicked by wind or passing animals up to a yard from the plant, caught on the coat of animals or dropped to the soil beneath the plant. Those in the soil may become attached to passing animals or vehicles. Seeds are also transported longer distances when carried by animals, man, or vehicles. Seeds are spread by water in rivers and along watercourses, and as a contaminant in crop seed and hay.

Spotted knapweed produces chemicals that help it compete with other plants for space. This makes it a very destructive exotic weed environmentally and economically. Spotted knapweeds release catechin into the soil through their roots. Catechin is an herbicide to most other plants, but not to spotted knapweed as its cells do not allow catechin to reenter once it is produced and released into the soil. The roots immediately generate and secrete catechin with the slightest stress for water or nutrients. The plant’s ability to produce, release, and protect itself from this chemical allows it to easily displace other weeds, native plants, and crops.

Management Methods

Prevention: Spotted knapweed reproduces by seed, so it is important that the production and spread of seed be limited as much as possible. Do not drive vehicles through infested areas. Nearly 2,000 seeds may be caught underneath a vehicle after driving through just one patch of knapweed, and up to ten percent of those can still be on the vehicle ten miles down the road. If you drive through an infested area, be sure to thoroughly clean the underside of your vehicle. Movement of soil material (sand, gravel, fill material, etc.) infested with spotted knapweed seed is another way this plant is spread.

Do not graze livestock on this weed during flowering once seeds are produced. Always use hay that is free of spotted knapweed seeds. Detect and eradicate weed introductions early, minimize soil disturbance, and contain neighboring infestations. It is essential to control outlying plants before attacking larger populations of the weed.

Mechanical Control: Careful and continual hand pulling can control small infestations of spotted knapweed. The entire plant must be removed each year before it produces seed in order to prevent regrowth. It is easiest and most effective to pull the plant when the soil is wet. Plants with seeds should be placed in plastic bags and disposed of by deep burial, or by burning in a hot fire.

Mowing when plants are in the bud to early flower stage will reduce spotted knapweed seed production, but rosettes escape mowing and the overall size of the infestation will not decrease. One timely mowing may be more effective than continuous mowing. Plants often reflower at a lower height and are able to escape the mower. The effects of mowing are likely dependent on the environmental conditions.

Cultivation to seven inches to sever the taproot may reduce spotted knapweed and promote grass growth.

A single, low-intensity fire is not hot enough to prevent resprouting from crowns or reestablishment from viable seeds in the soil, and therefore does not effectively control spotted knapweed. The disturbance caused by fires may actually encourage the colonization of knapweeds. Burning the plants before applying an herbicide may, however, increase the effectiveness of the treatment as the regrowth will be very uniform.

Cultural Control: Rigorous defoliation will reduce root, crown, and above ground growth of spotted knapweed. Livestock and wildlife will generally not graze spotted knapweed because of its bitter taste unless forced to for lack of other feed. Spotted knapweed rosettes and young flower shoots have some nutritional value, but they are difficult for cattle to eat because they are so close to the ground. Mature knapweeds are less desirable because they are fibrous and coarse with rough flowering stems and spines on the floral bracts.

Low to moderate levels of grazing by cattle, sheep, and goats can be used. However, cattle seem to prefer grasses to spotted knapweed, which can favor spotted knapweed development over grasses because of reduced competition. With time and continued cattle grazing, spotted knapweed will become more competitive.

Limited grazing, and repeated grazing by sheep when grasses are dormant, may reduce seedlings and rosettes and reduce reproduction but will not have an impact on older and larger plants.

If there is desirable grass competition in spotted knapweed stands, grazing and a careful application of an herbicide that does not harm the grasses will allow the grasses to more effectively compete with the weeds. Irrigation may also help encourage grass competition.

Biological Control: A variety of biological control agents have been released for control of knapweeds. They add stresses to the plant which reduces seed production and the competitiveness of knapweeds; however, they are more effective if used in combination with other methods.

The larvae of two seedhead feeding flies (Urophora affinis and U. quadrifasciata) can reduce seed production of spotted knapweed by as much as 50 percent when released together. These are the most widely distributed biocontrol agents for spotted knapweed. The flies have not, however, had a prominent effect on the population of the weed because of the high number of seeds produced per plant.

One larva of the knapweed peacock weevil, Chaetorella acrolopii, can destroy the entire content of a flower head.

The larvae of Bangasternus fausti, the broad-nosed seedhead weevil, mine the leaf and stem before moving into the seedhead where they may consume 95 percent of the seeds.

A newer agent, Larinus minutus, the lesser knapweed flower weevil, is a seedhead weevil that has been introduced to parts of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. It has reportedly provided excellent control of spotted knapweeds in these locations. The larvae are aggressive and will kill other insects in the same seed head.

Larvae of the spotted knapweed seedhead moth Metzeneria paucipunctella, feed on the flowers and seeds of spotted knapweed, reducing the seed production by about 20 percent.

A root moth (Agapeta zoegana) and a root weevil (Cyphocleonus achates) damage the roots of spotted knapweed plants. Larvae of the sulfur knapweed moth, Agapeta zoegana, damage spotted knapweed by mining its crown and roots. Weakened plants may not flower.

The gray-winged root moth, Pterolonche inspersa, and the bronze knapweed root borer, Sphenoptera jugoslavica, both attack the crown and roots, interrupting the vascular system and depleting stored energy reserves.

Fungal and bacterial pathogens also infect spotted knapweed. A soil fungus (Sclerotinia sclerotiorum) causes wilting and sometimes death. The bacteria Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae has also been found attacking spotted knapweed.

Chemical Control: Control of knapweeds with herbicides can be effective if used in combination with other control methods. Annual treatments for several years will be needed. The latent seed from previous years will germinate and reestablish the infestation if not controlled with follow-up treatments. Establishing a competitive crop or sod, such as a perennial grass, will enhance control of any regrowth and deter the establishment of new seedlings.

The most effective treatment is to apply Tordon® (picloram) to knapweed plants in late spring before or during flower stem elongation at a rate of 0.25 to 1.5 lb ai/A. This rate will provide four years control and will not damage perennial grasses. Treatment of plants in the bud stage may not prevent seed production in the year of application, but seed germination will be noticeably reduced. Tordon® is a restricted-use herbicide that must be applied by, or its application supervised by, a certified pesticide applicator.

Glyphosate effectively controls knapweed plants, but will also destroy competitive grasses and forbs. If using glyphosate, apply to actively growing plants in the bud stage at a rate of 3 lb ai/A. Seed a locally adapted grass at least ten days after the application.

After most rosettes have emerged, but before flower stems elongate, knapweeds can be treated with 2 to 5 quarts/A of Curtail® (clopyralid plus 2-4D amine) for up to two years control.

Stinger® (clopyralid) or Transline® (clopyralid) can be applied to knapweeds up to the bud stage of growth. The best results will be obtained if actively growing weeds are treated. The recommended rate of application for knapweeds is 0.5 to 1.33 pints/A which, should give two years control.

Summary

Spotted knapweed is an invasive, noxious weed that should be prevented from invading lands in Nevada. It can be successfully managed over time using a variety of integrated measures if addressed in an aggressive, consistent manner using the best knowledge about control methods available.

References

Ball, D.A., D. Cudney, S.A. Dewey, C.L. Elmore, R.G. Lym, D.W. Morishita, R. Parker, D.G. Swan, T.D. Whitson and R.K. Zollinger. Weeds o the West. 9th edition, Western Society of Weed Science. 2001.

Beck, K.G. Dffuse and Spotted Knapweed. No. 3.110. Colorado State University Cooperative Extension. 18 Feb. 2004.

Lacey, C.A., J.R. Lacey, P.K. Fay, J.M. Story, and D.L. Zamora. Controlling Knapweed on Montana Rangeland. Montana State University Extension Service. July 1999.

Moser, L. and D. Crisp. Knapweed Information Page. San Francisco Peaks Weed Management Area. 18 Feb. 2004.

Rees, N.E., P.C. Quimby, Jr., G.L. Piper, E.M. Coombs, C.E. Turner, N.R. Spencer and L.V. Knutson, eds. Biological Control of Weeds in the West. Western Society of Weed Science, Bozeman, MT, 1996.

Sheley, R.L., and J.K. Petroff, eds., Biology and Management of Noxious Rangeland Weeds. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 1999.

William, R.D., A.G. Dailey, D. Ball, J. Colquhoun, T.L. Miller, R. Parker, J.P. Yenish, T.W. Miller, D.W. Morishita, P.J.S. Hutchinson, and M. Thompson. Pacific Northwest Weed Management Handbook. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University, 2003.

“Colorado State University Identifies Natural, Plant-Produced Herbicide.” Agriculture News at Colorado State University. 25 June 2002.

Centaurea maculosa, C. diffusa—Spotted and Diffuse Knapweed. Wildflowers and Weeds. 18 Feb. 2004.

Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea maculosa). Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. 18 Feb. 2004.

Photographs are courtesy of Weeds of the Wes.

Information herein is offered with no discrimination. Listing a product does not imply endorsement by the authors, University of Nevada Cooperative Extension (UNCE) or its personnel. Likewise criticism of products or equipment not listed is neither implied nor intended. UNCE and its authorized agents do not assume liability for suggested use(s) of chemical or other pest control measures suggested herein. Pesticides must be applied according to the label directions to be lawfully and effectively applied.

Graham, J. and Johnson, W.

2004,

Managing Spotted Knapweed,

University of Nevada Cooperative Extension