Introduction

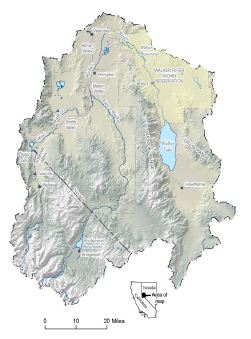

Nestled on the leeward side of the Sierra Nevada range lies a watershed containing one of the few perennial, natural and terminal lakes in the Great Basin. This lake, and the sources that supply it, comprise the Walker River Basin.

Originating as snowmelt high in the mountains across the border in the state of California, the East and West Walker tributaries merge approximately eight miles south of Yerington, Nevada to form the Walker River. From there, the river travels northeast, where it rounds Parker Butte and turns south through Weber Reservoir, eventually terminating in Walker Lake.

The water within the basin is vital to the region, serving a multitude of activities and needs, including agricultural use, recreation, human consumption and environmental sustainability. Since the 1880s, the level of these water uses has been increasing and the availability of water decreasing.

In more recent years, the decisions facing water rights owners have become difficult and complex. In 2003, a survey of water rights owners was conducted to better understand the issues of which they are most concerned and to assess their willingness to sell or lease their water rights within the Walker River Basin. The study was conducted using written surveys administered in person to 116 water rights owners in the region. In 2007, a “follow-up” study mailed written surveys to landowners in the Walker River Basin. This more recent study consisted of 70 completed surveys, representing 22 percent of the surveys that were distributed.

This fact sheet will provide a background on water rights in Nevada, followed by a comparison of the survey findings between 2003 and 2007. This comparison seeks to examine the changes in water rights owners’ willingness to sell or lease their holdings.

Nevada Water Rights

The regulation of water rights in Nevada is outlined in Chapters 532 through 541 of the Nevada Revised Statutes, which includes the key doctrine of Prior Appropriation. It is under this principle and these regulations, administered by the State Engineer, that the Nevada water market operates.

Prior Appropriation is commonly referred to as “first in time, first in right,” meaning that a right to water acquired earlier in time is superior to a similar right acquired later in time (Nevada Division of Water Resources, 2008). While superiority of rights has no bearing as to what the usage of the water will be, a user who is the first to take a quantity of water and put it to “beneficial use” has a higher priority of right than subsequent users (Nevada Division of Water Resources, 2008). Water rights can be lost through nonuse and can also be sold or transferred separately from the land to which they are attached.

Beneficial use is defined by the Nevada Division of Water Resources as “A use of water resulting in appreciable gain or benefit to the user, consistent with state law…” and “a use of water that is, in general, productive of public benefit, and which promotes the peace, health, safety, and welfare of the people of the State.” Activities that have qualified as beneficial use include commercial development, construction, drilling, industrial use, irrigation, milling, mining, municipal use, power generation, recreation, stock watering, storage, and wildlife conservation.

The system for water regulation within the Walker River Basin provides for four main types of water rights: federal decree, storage, primary and supplemental. Decree rights are those granted by a court or arbiter after an application or grievance meets both prior appropriation and beneficial use requirements. Storage rights are granted to agencies or individuals to impound and store water for specific purposes. While both decree rights and storage rights generally apply to surface water, primary and supplemental rights are utilized in the management and allocation of groundwater. Primary rights are those granted for use of groundwater as the primary source of the resource and are regulated by the State of Nevada. Supplemental rights, similar to primary rights, are also regulated by the State of Nevada and are allocated for the use of groundwater as an addition to other, pre-existing water rights.

Survey Results

The figures and tables on the following pages represent total frequencies of responses for each question. Each value is the total percentage of responses for each option in the given year. All tables show the total number of respondents falling into that category in the final column.

Willingness to Sell

Survey respondents were asked to indicate whether they would be willing to sell their water rights in the future (Figure 1). In both 2003 and 200y, the majority of water rights owners surveyed indicated that they were reluctant to sell their water rights, saying that they would “definitely not sell” or would “prefer not to sell,” with the overall frequency of such responses increasing by 24 percentage points from 2003 to 2007. The total frequency of respondents considering selling their water rights dropped from 17 percent in 2003 to just four percent in 2007. It should be noted that those participating in the 2003 survey were given the option of not answering the question, while the 2007 survey takers were not.

Figure 1: Respondents’ Willingness to Sell Water Rights, 2003 and 2007

*table here

The responses to the question of whether owners were willing to sell their water rights were further examined based on the number of years the owner or the owner’s family had lived in the Walker River Basin (Table 1). Of the respondents whose families had lived in the Walker River Basin for more than 25 years, in 2007 64 percent said that they would definitely not sell their water rights, an increase of 13 percentage points over 2003. For respondents who had lived in the area for less than 25 years, the total percentage of respondents who would definitely not sell their rights increased 18 points from 2003 to 2007, going from 28 percent to 46 percent. In both 2003 and 2007, no respondents who had lived in the region for more than 25 years were definitely willing to sell their water rights.

Respondents whose families had lived in the area for less than 25 years more frequently indicated that they were undecided in whether to sell their holdings.

Table 1: Respondents’ Willingness to Sell Water Rights by Years in Walker River Basin

*table here

Respondents’ willingness to sell their water rights was also analyzed by whether or not the respondent was involved in agricultural production and for how long (Table 2). Sixty-five percent of water rights holders involved in agriculture for more than 35 years said they would definitely not sell on the 2007 survey, an increase of five percentage points over 2003. Overall, more respondents in both groups were increasingly reluctant to sell their water rights in 2007 relative to 2003, however, the greatest shift in reluctance was seen among those involved in agricultural production for less than 35 years, with a 26 percentage point difference in those indicating that they would definitely sell, consider selling or were undecided about selling.

Table 2: Respondents’ Willingness to Sell Water Rights by Years in Agriculture

Willingness to Lease

Survey respondents were also asked to indicate how willing they were to lease the water rights they held. Again, those participating during the 2003 survey were offered the option “no answer,” while those in the 2007 study were not.

In 2003, 35 percent of respondents indicated that they would consider leasing, a much larger frequency than the 17 percent in 2007 (Figure 2). Additionally, the number of respondents considering leasing their rights was 18 and 13 points greater than those considering selling in 2003 and 2007, respectively. Between the two years, the total frequency of respondents who would definitely lease stayed relatively equal, while those reluctant to lease (stating that they preferred not to lease or definitely would not lease) experienced an increase of 28 percentage points.

Figure 2: Respondents’ Willingness to Lease Water Rights, 2003 and 2007

*table here

As with the results for willingness to sell, the frequency of “undecided” respondents in regards to leasing water rights decreased by nearly half from 2003 to 2007, dropping from 13 percent in 2003 to seven percent in 2007 (Table 3). Among those respondents whose families had lived in the region for less than 25 years, the percent of “undecided” and “considering leasing” responses dropped dramatically between 2003 and 2007, with decreases of 19 and 29 percentage points, respectively. The total frequency of long-time inhabitants indicating that they would consider leasing also decreased, dropping by 29 percentage points between 2003 and 2007.

Surprisingly, in 2007 those living in the area for less than 25 years surpassed the other group by five percentage points in the total frequency of “definitely not leasing” responses. In 2003, the frequency of such a response among respondents living in the area for less than 25 years was nine percentage points less than those who had been there for a longer period of time.

Table 3: Respondents’ Willingness to Lease Water Rights by Years in Walker River Basin

*table here

The results are similar when examined by number of years in agricultural production practices, although not to the same magnitude (Table 4). While the total number of “considering leasing” responses was higher in both studies for those in agriculture less than 35 years, in 2007 the difference in frequency of such a response between this group and those involved for more than 35 years lessened. In 2003, the difference was six percent, while in 2007 it dropped to two percent. While respondents new to agriculture did not have a higher frequency in the number of “definitely not leasing” responses, they did show greater frequency in “prefer not to lease” responses than those in agriculture for more than 35 years.

Table 4: Respondents’ Willingness to Lease Water Rights by Years in Agriculture

*table here

Conclusions

For both categories (years involved in agricultural production and years living within the basin) shifts towards reluctance to lease or sell water rights appear to be similar amongst the time-period groups. This would indicate that the shift in the perception of incentives to sell or lease water rights has changed to the same degree for both those in the region or involved in agriculture for many years, and those in the region or involved in agriculture for fewer years. However, the data also indicates that rights holders who have been in agriculture for more than 35 years or living in the region for more than 25 years were more likely to definitely not sell or lease water rights than their counterparts for both years.

Overall, fewer water rights owners in the Walker River Basin were willing to sell or lease their rights in 2007 than in 2003. Also in 2007, fewer respondents indicated that they were “undecided” in whether or not to sell or lease their water rights. This movement signifies that since 2003 rights owners are actively making decisions regarding the management of their water rights. Finally, survey responses indicate that in both years those holding water rights were more willing to lease rights than they were to sell them.

More Information

University of Nevada Cooperative Extension has additional publications relating to water rights, the Walker River Basin, and more. These publications can be found online at University of Nevada Cooperative Extension Pubs.

References

Emm, S., D. Breazeale, and M. Smith (2005). “Walker River Basin Research Study: Willingness of Water Right Owners to Sell or Lease Decree Water Rights.” University of Nevada Cooperative Extension Fact Sheet FS-05-54.

United States Geological Survey Nevada Water Science Center. “Hydrology of the Walker River Basin.” Online. Available at Hydrology of the Walker River Basin Accessed May 2008.

State of Nevada Division of Water Resources. “Water Words Dictionary.” Online. Available at: Water Words Dictionary Accessed May 2008.

Curtis, K., Emm, S., and Entsminger, J.

2008,

Landowner Willingness to Sell or Lease Water Rights in the Walker River Basin,

University of Nevada Cooperative Extension