Once the monitoring data are collected, they must be analyzed along with other useful data and information. Analysis includes organizing, summarizing, analyzing and evaluating the validity and utility of information in order to make a decision. Because it is often preferable in planning and monitoring to use a collaborative approach, analysis of monitoring data should also be collaborative. This is especially true if different people collect different parts of the whole data set. For example, if the permittee collects short-term monitoring data, and agencies collect long-term data, collaborative analysis increases and shares understanding. The permitte(s) is (are) an integral part of the process of development of conclusions to better understand management practices and conditions for particular site(s) and season(s) of use. Conclusions about progress toward objectives and causes of meeting or not meeting objectives are both essential and must be thoroughly reasoned based on all available information. For application to public lands, the rationale for management changes (or not) must be documented.

Management involves not only predicting how ecological or physical systems are likely to respond to management actions, but also identifying what management options are available, what outcomes are desired, how much risk can be tolerated, and how best to choose among a set of alternative actions. State and transition models in ecological site descriptions along with short- and long-term monitoring informed by the lessons from Nevada Range Management School (McAdoo et al. 2010) help managers choose to continue existing management, change management or change objectives. In many areas, past objectives based on range condition or seral stage should be modified to reflect modern ecological and management thinking. The challenge confronting managers is to make “good” decisions in a complex situation. Therefore, the quality of decision-making in the face of uncertainty should be judged as much by the decision-making process as by the progress toward desired outcomes.

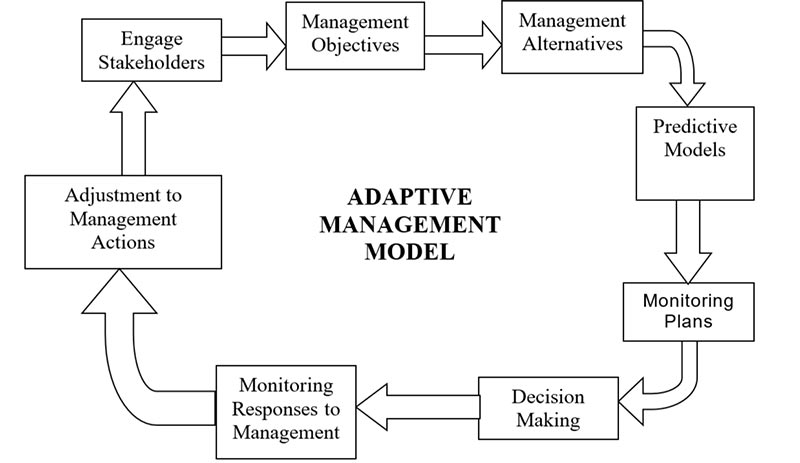

“For many important problems now facing the resource management community, adaptive management holds great promise in reducing the uncertainties that limit the effective management of natural resource systems. For many conservation and management problems, utilizing management itself in an experimental context may be the only feasible way to gain the system understanding needed to improve management. An adaptive approach actively engages stakeholders in all phases of a project over its time frame, facilitating mutual learning and reinforcing the commitment to learning-based management.” (Williams, Szaro and Shapiro 2007).

Adaptive management for riparian areas is described in Dickard et al. (2015), Swanson et al. (2015), and Swanson (2016) as “integrated riparian management.” it includes seven steps. See Appendix E – Characteristics of Good Objectives.

Figure 47. This adaptive management model includes some steps needed and implied in other flow charts: engaging stakeholders, considering alternatives and predicting results to determine how the objectives and strategies should be monitored.

Figure 47. This adaptive management model includes some steps needed and implied in other flow charts: engaging stakeholders, considering alternatives and predicting results to determine how the objectives and strategies should be monitored.