Introduction

Living in the Great Basin requires that residents deal with many different natural events such as range fires, flash flooding, and insect infestations. Mormon crickets (Anabrus simplex) have been a problem historically and over the last few years. The purpose of this fact sheet is to provide residents with pertinent information about Mormon crickets, their life cycle, and a variety of control measures that may reduce damages to their property.

Mormon crickets are flightless, grounddwelling insects native to the western United States. They eat native, herbaceous perennials (forbs), grasses, shrubs, and cultivated forage crops, reducing feed for grazing wildlife and livestock. In large numbers, their feeding can contribute to soil erosion, poor water quality, nutrient depleted soils, and potentially cause damage to range and cropland ecosystems.

Drought encourages Mormon cricket outbreaks, which may last several years (historically 5 to 21 years) and cause substantial economic losses to rangeland, cropland, and home gardens. This is particularly true as adults and nymphs of Mormon crickets migrate in a band, eating plants along their path.

Mormon crickets occur in rangelands west of the Missouri River and statewide in Nevada. Their populations are cyclic over many years.

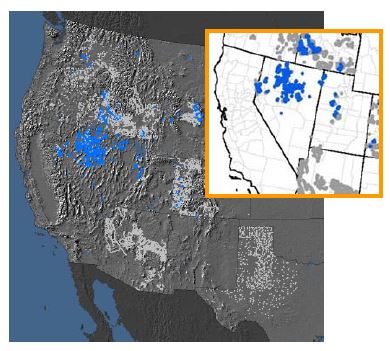

Since the late 1990s, their population has been increasing, particularly in Nevada (Figure 1). The greatest numbers occupy lands north of Tonopah, Nevada. In 2006, approximately ten million acres in Nevada were infested with Mormon crickets.

Figure 1. National distribution of Mormon crickets, August 2005 (blue = high density, gray = low density)

Control efforts have increased in recent years as favorable conditions for the crickets have stimulated increased growth in their population. To reduce their numbers within communities and farmlands, and to provide for public safety along the Interstate 80 and Highway 50 corridors, the Nevada Department of Agriculture has applied Dimilin, a restricted use insect growth regulator, and baits containing the pesticide carbaryl (Sevin®) to thousands of acres for the past several years.

Identification

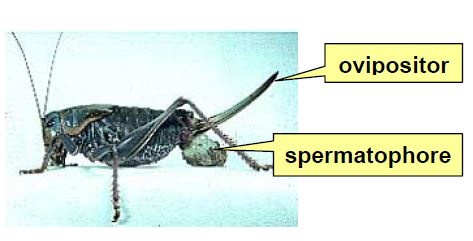

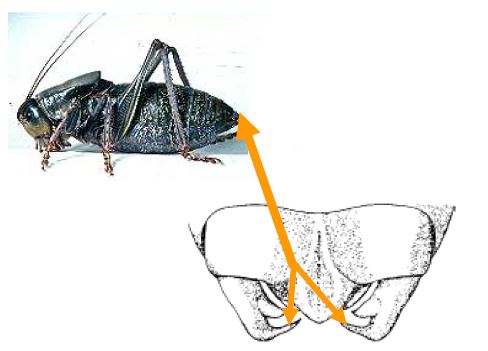

Mormon crickets are not true crickets; they are shield-backed, short-winged katydids that resemble fat grasshoppers that cannot fly. Adults and nymphs of Mormon crickets have long antennae and a smooth, shiny exoskeleton in a variety of colors and color patterns. The adult female has a spermatophore (sperm holding sack) for a short time after mating and a long ovipositor (egg layer) with a gentle upward curve (Figure 2). The male cercus (appendage at the posterior end of the abdomen) has two large teeth (Figure 3). Adult Mormon crickets are 1 ½ to 2 inches long.

Figure 2. Adult, female Mormon cricket with ovipositor and spermatophore.

Figure 3. Adult, male Mormon crickets have paired cerci, dorsal view below.

Life Cycle

Eggs are laid singly in the summer and are dormant through winter. Mormon cricket eggs hatch and nymphs emerge in the early spring when soil temperatures reach 40°F. At higher elevations where the soil remains cold, eggs may incubate an additional year.

Mormon crickets pass through eight growth stages (instars―seven as nymphs, one as an adult) within 60 to 90 days depending on temperatures and other environmental conditions. First instar nymphs are about ¼ inch long and tend to be black with a white stripe (Figure 4). Older nymphs vary in color from black to various shades of brown, orange, and green.

Figure 4. A first instar Mormon cricket (right) has a white band behind its head.

Mormon crickets molt in 10 to 20 minutes, hanging on plants in the sun while their new exoskeleton dries, darkens, and becomes hard. Before crawling away the insect eats its old, cast-off skin (exoskeleton). Courting and mating begin 10 to 12 days after becoming adults.

Habitat and Conflicts

Large resident populations of this species develop in open sagebrush-forb-grass habitats of the Intermountain West, up to 11,000 feet in elevation. In the past, homesteads, and today, new subdivisions and individual homes, occupy traditional Mormon cricket habitat, creating conflicts between crickets and property owners over damage to crops and landscapes that may be costly or at least a nuisance.

Food and Feeding Damage

Although Mormon crickets feed on more than 400 species of plants, succulent forbs are preferred. Migrating bands damage forage plants (rangeland forbs, grasses, and shrubs including dandelion, mustards, pepper-weeds, bluegrass, penstemon, and sagebrush), small grains, alfalfa, and most other crops. Home gardens and landscapes are also damaged including vegetable gardens, flowers, ornamentals, and lawns.

Not only do Mormon crickets eat plants causing damage or economic loss, their presence in doing so may be detrimental. Structures and hardscapes may be superficially stained with feces or crushed crickets, creating a clean-up cost to property managers of condominiums, parks, golf courses, etc., or home owners. In the case of forage crops, the quality of the hay produced is reduced if it is full of baled or chopped-up Mormon crickets. In some cases, where the number of crickets in the hay is extreme, the hay is not saleable.

Dispersal and Migration

Mormon crickets have a migratory habit, staying at one site usually three or four days. As flightless insects, they crawl and hop, moving during favorable conditions, mainly in daylight hours when skies are clear and temperatures range between 65°F to 95°F. They seek shelter under plants and remain inactive when conditions are very hot, cloudy, and cold. They also stop at night, unless it is warm, in which case they may move.

During the first four instars, Mormon crickets are usually individually mobile, moving short distances to seek food and shelter, but even then, they often form bands. Older instars and adults move together in migrating bands, in one direction, consuming vegetation across an area. They may travel one-half to one mile a day and 25 to 50 miles per season. Separate bands may join into a larger band or two bands may flow through one another, each continuing its established course. Historically, high population densities have lasted five to 21 years. This is the seventh year (2006) of the present infestation in some parts of northern Nevada.

Management for the Property Owner

Physical/Mechanical: While it is not usually feasible for an individual to protect large land areas, yards and gardens can occasionally be physically protected. Where possible, home owners can erect a fence or slick barrier 18-24 inches high (chicken wire covered tightly with sheet plastic) around valuable ornamentals, flowers beds, and gardens. Mormon crickets normally cannot walk up a slick barrier placed in a vertical position. If a few Mormon crickets enter a home or building, they may be vacuumed into a disposable bag. Seal the bag and dispose of it in the trash.

Biological Control: Natural predators include wild birds and poultry. A black wasp (Palmodes laeviventris) present in a few northern Nevada rural communities in 2006 is also reported to be the major cricket predator. A parasite (Varimorphan sp.) occurs naturally in populations of Mormon crickets and in the early nymphal stages can be devastating when the parasite is present in high numbers. Unfortunately, this parasite only occurs naturally and is not commercially available at present.

Cultural: During fall clean-up, home owners should rake their lawns and turn over or till soil in their garden beds to expose the eggs. Cold temperatures will not allow egg hatching. Exposure to daily heating and freezing will dehydrate the exposed eggs, killing them.

Chemical: Carbaryl (Sevin®) bait may be applied around the perimeter of properties, such as fields, gardens, and landscapes as a protection. Bait can usually be purchased by home owners from private suppliers. Other pesticides including insect growth regulators, are also available. Choose an insecticide or growth regulator based on the age of the cricket population, forage conditions, and whether or not the product is registered for application to the crop or site. Weather, other environmental factors that could impact the product’s application, available manpower, equipment, and economic resources, as well as the risks to the applicator, other workers, and the environment associated with its use should be considered.

Mormon crickets cannibalize their dead and injured. Consequently, carbaryl bait ingested by one Mormon cricket that dies may kill a second or third with subsequent feeding among the horde.

Non-Chemical Bait: For those concerned with the use of traditional pesticides, there are general use products registered for application around the home: PERMA-GUARD Garden and Plant Insecticide (D-21). D-21 is a diatomaceous earth-based product that kills insects by puncturing their exoskeleton, causing them to die from dehydration. The authors have not seen any empirical data supporting its effectiveness in killing Mormon crickets, but the manufacturer claims that D-21 is just as effective as carbaryl bait and without any harmful side effects to animals, humans, or the environment.

Economics: In commercial agriculture, Mormon crickets have the potential to cause great financial losses. Fortunately, during the infestations in Nevada over the last several years, there have not been many reported cases of extensive crop damage. However, for alfalfa and other hay producers, even though the crickets may not cause great damage from eating or chewing the plants, hay containing large numbers of crickets becomes unpalatable to livestock when harvested. With hay prices at approximately $100 a ton or more, infestations have the potential to cause great economic damage to the industry even though the crop may not have been eaten by the crickets.

Agency Contact

Anyone finding Mormon crickets is encouraged to report them to the Nevada Department of Agriculture.

Pesticide Safety and Information

For further information, contact a representative of the University of Nevada, Extension.

References

- Freshwater Organics, LLC. Retrieved June 30, 2006.

- Nevada Agricultural Statistics. September 2005. U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Nevada Department of Agriculture.

- Skelly, J., W. Johnson, W. Riggs and J. Knight. 2002. Field Guide to Grasshoppers of Economic Importance in Nevada. University of Nevada Cooperative Extension, Extension Bulletin 02-02.

- Pallares, M. July 2005. Mormon Crickets Entering Alfalfa Fields, The Nevada Rancher, Lovelock, NV.

- Willms, M. July 2004. Cricket Infestation Growing, The Nevada Rancher. Lovelock, NV.

- Sword, G. 2006. Mormon Cricket Management, USDA-ARS NPARL, Sidney, MT.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. May 2003. Grasshoppers and Mormon Crickets – Fact Sheet. Washington, DC.

- Pfadt, R.E. 1994. Mormon Cricket Anabrus simplex Haldeman. Wyoming Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 912. Sidney, MT.