Introduction

American Indians of the western range refers to American Indians who reside in a region of the western U.S. bordered on the west by the Sierra and Cascade mountains and on the east by the Rocky Mountains (Woodhead, 1995). The western range includes the Columbia Plateau and Great Basin cultural and physiographic areas.

This fact sheet briefly describes early cultural attributes unique to the indigenous people of these areas. Professionals working on reservations are encouraged to learn as much as possible about individual reservations and tribes with respect to origin, history and culture.

Early Culture and Lifestyle

Much of the knowledge about early indigenous cultures stems from speculative reconstructions by Euro-American explorers after their initial contact with indigenous peoples.

Early American Indians of the western range were a survivalist culture, which necessitated a semi-nomadic lifestyle. That is, during the winter they resided in permanent lodges and consumed foods they prepared and stored for the cold winter months. During the remainder of the year, they moved among established camps in rhythm with the change of seasons to hunt and gather food (Hunn, Turner & French, 1998).

In recent geological terms, the Great Basin is primarily high desert, open arid land with alkaline soils. Although the Great Basin receives little precipitation, its basin-and-range topography provided indigenous peoples with small game as well as nuts and seeds from the tree-lined mountain ridges. Its lowland perennial streams and marshes provided various water fowl, such as ducks and mud hens, and eggs. Small game consisted of jack rabbits primarily with occasional deer and mountain sheep. While northern Great Basin Indians hunted mountain sheep in addition to elk and deer, central Great Basin Indians relied more heavily upon rabbit supplemented occasionally with whitetail deer.

In contrast, the Columbia Plateau farther north featured a more varied environment ranging from coniferous forests to lush mountain meadows and bunch grasses. Its forests supplied elk and bear, while its plateau grasses provided rabbit, deer and antelope. Native plants provided an important food staple for western range peoples. A variety of wild vegetables were consumed, including wild carrot, onion, dandelion and spinach.

Both Plateau and Great Basin peoples relied heavily on roots of the camas plant. They constructed tools to dig for roots, including wooden sticks, often with antler horns for handles. Columbia Plateau Indians harvested a large variety of wild berries, including huckleberry, chokecherry and strawberries while Great Basin Indians harvested seeds and pine nuts primarily.

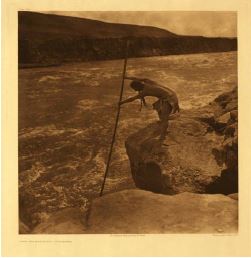

Archaeological evidence, including artifacts such as handmade hooks, nets and traps, suggests that the majority of early western range Indians relied heavily upon fish. Indians located farther upstream and inland who relied more upon rabbit, deer and elk traded animal skins and camas roots for salmon harvested and dried by tribes located closer to salmon runs (Boyd, 1998). Similarly, Great Basin Indians fished the rivers and terminus lakes of their rugged high desert homeland. In northern and central Nevada, the rivers running through these lands originated as streams fed by snow melt from the surrounding Sierra Nevada. These include the Truckee, Carson, and Walker rivers. The people living along these rivers and terminus desert lakes relied upon various species of trout in addition to large bodied sucker fish such as cui-ui.

Fish provided a diet staple for early Indians.

During the spring, summer and fall Indians throughout the western range convened at major deltas and similar points along the Columbia River to enjoy bountiful fish harvests. Indians who attended these gatherings traded goods, such as herbs, dried meats, animal skins, obsidian arrow heads, hand-made tools, woven baskets, shells and beads. The gatherings also provided a range of social opportunities, including gambling, games, dancing, courtship, marriage and ceremonies.

Early Housing

Early Indians throughout the western range lived and travelled as bands. Typically these bands consisted of one to a few families related by marriage, or kin-cliques.

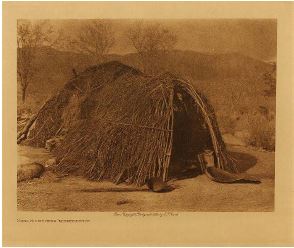

Accounts of early explorers described the winter lodges of Great Basin Indians, or wiki-ups, as hemispherical-shaped lodges. To build the support frame, they lashed together native willow saplings, leaving a hole at the top for smoke and an opening at the east side for an entrance. They covered the frame with a thick thatch of dried piňon needles and sometimes covered the thatch with earth as well as sealed the bottom of the structure with earth and mud. Summer homes near fishing areas included shade houses primarily and were constructed of willow boughs and sage brush (Curtis, 1911).

Native plants were used to construct homes.

Many early Columbia Plateau Indians lived in permanent longhouses which were rectangular-shaped, supported with lodgepole pine frames and covered with mats woven from tule bulrush that grew in riparian areas. The tule reeds provided insulation during the winter and allowed the house to breath in the summer. Large numbers of families, typically related by marriage, shared these lodges with each family having a designated area for fire, cooking and sleeping.

Smaller, conical shaped structures of the same materials were also constructed to house nuclear families. After adoption of the horse, many Plateau Indians constructed their lodgings from animal skins and later canvas, instead of tule mats, which provided a lighter, more easily transportable lodge.

Basket-maker Culture

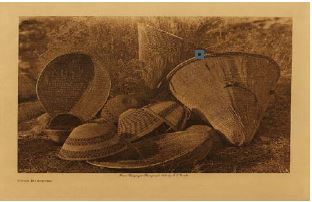

Anthropologists refer to the early Indians of the western range as a basket maker culture. Baskets were essential tools used to harvest and process plants and seeds as well as to transport medicine, food and personal belongings. Western range Indians wove baskets from available native plants. In the northern Great Basin, Indians made their baskets from willows that grew along the riverbanks, gathering them beginning in the fall and ending in the spring. They sealed willow baskets with the pine tar from the local piňon trees in order to use the baskets to carry and store water.

For the Plateau Indians, materials for basket weaving involved a variety of native plants, including bear grass, cedar root, cedar tree bark, Indian corn husks and hemp. Columbia Plateau Indians invested significant time during the winter producing hemp cord which they used in the construction of tule mats for housing, bedding and flooring in addition to the construction of other baskets, bags and hats (Miller, 1998). Soft bags, referred to as ‘sally bags’, were constructed to collect roots and likely as objects of personal adornment. Similarly, Columbia Plateau Indian women wove and wore soft, yet structured, basket hats which served as protection from cold, wind, dust, rain, and the head straps used to bear burdens on their backs, such as cradle boards. Basket hats likely served as objects of personal adornment as well (Schlick, 1994). The middle region of the Columbia River in particular features some of the best examples of Indian basketry in North America.

Baskets were essential survival tools.

Language

The majority of the early Indian peoples within the Columbia Plateau region spoke a dialect of the Sahaptin language family. Speakers of the Salish language family settled to the north and east of Sahaptin speakers in modern-day Canada (Kinkade, et al., 1998). The Great Basin Indians spoke dialects of the Uto-Aztecan language family. This rather large language family includes languages still spoken by millions of descendents of the ancient Aztec civilization who live in central Mexico and in parts of Guatemala, and Central America (Miller, 1986).

As is the case with many American Indian tribes, native language is disappearing with fewer tribal members, mainly elders, able to speak their native tongue. Over the past several decades, tribal governments and schools in the Plateau and Great Basin regions have made concerted efforts to rekindle an interest in and pride in cultural heritage, with a focus on native languages. Several reservations have established native language programs either as part of their school curriculum or as extracurricular learning programs.

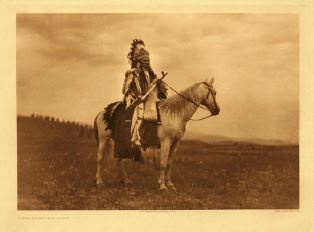

Influence of the Horse

Some anthropologists attribute much of the significant changes to Columbia Plateau Indian culture that occurred between 1600 and 1750 to the influence of the horse rather than interaction with non-Indians. Plateau Indians were able to travel greater distances to hunt bison cooperatively with Plain tribes, frequently adopting the customs and dress of Indians with whom they intermingled. Due to its harsh climate and environment, Great Basin Indians adopted the horse comparatively later, during the 18th century. However, once they adopted the horse, Great Basin Indians quickly expanded their seasonal hunting patterns and trade activities with tribes far away from their ancestral grounds (Shimkin, 1986). The horse was such a powerful influence on Indians that the Columbia Plateau Indians, in particular, became known as a horse culture. Significant and sincere respect for the horse remains apparent throughout the western range Indian culture today. Many contemporary reservation events and celebrations continue to feature horseback-riding sports and activities, including Indian ceremonial costumes and regalia designed especially for horse and rider.

Columbia Plateau tribes became expert horse breeders.

Summary

This fact sheet provides a brief overview of the early culture unique to the American Indians of the western range, the Columbia Plateau and Great Basin. The purpose of this fact sheet is to increase awareness and appreciation of cultural attributes that distinguish American Indians in this geographic region. Professionals working on reservations are encouraged to learn as much as possible about individual reservations and tribes with respect to origin, history and culture.

References

Curtis, E.S. (1911). The North American Indian. Northwestern University Library. Retrieved May 9, 2008 from The North American Indian

Hunn, E.S., Turner, N. J., & French, D. H. (1998). Ethnobiology and Subsistence, in Deward E. Walker, Jr. (Volume Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plateau (Vol. 12), pp. 525-545. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Kinkade, M.D., Elmendorf, W.W., Rigsby, B., & Aoki, H. (1998). Languages, in Deward E. Walker, Jr. (Volume Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plateau (Vol. 12), pp. 49-72. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Miller, J. (1998). Middle Columbia River Salishans, in Deward E. Walker, Jr. (Volume Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plateau (Vol. 12), pp. 253-270. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Miller, W.R. (1986). Numic Languages, in W. L. D’Azevedo (Volume Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Great Basin (Vol. 11), pp. 98-106. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Schlick, M.D. (1994). Columbia River Basketry: Gift of the Ancestors, Gift of the Earth. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Shimkin, D.B. (1986). Introduction of the Horse, in W. L. D’Azevedo (Volume Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Great Basin (Vol. 11), pp. 517-524. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Woodhead, H. (1995). Indians of the Western Range. Richmond, VA: Time-Life Books.