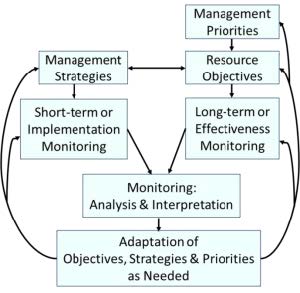

The Nevada Rangeland Monitoring Handbook (Swanson et al. 2018) emphasizes that short-term or implementation monitoring should focus on the strategies planned or employed to accomplish resource objectives (Figure 1).

Figure 1. This Framework for Monitoring in Swanson et al., (2018) begins short-term or implementation monitoring by focusing on management strategies aligned to meet resource objectives.

Figure 1. This Framework for Monitoring in Swanson et al., (2018) begins short-term or implementation monitoring by focusing on management strategies aligned to meet resource objectives.

While the first edition (1984) emphasized utilization to avoid overgrazing, the second and third editions (Swanson et al. 2006 and 2018) introduce the grazing response index to consider a more robust list of grazing effects on rangeland plant growth (Reed et al. 1999; Swanson et al. 2019). The index considers the frequency and intensity of grazing and opportunity for growth and regrowth. Frequency, intensity and opportunity all focus on the growing season and the combined score is intended to reflect the quality of grazing management in relation to the needs of plants to grow and thrive. Ranchers may strive for a positive score each year or for a positive average of scores across years.

As useful as the index may be for evaluating or considering the effects of grazing on perennial grasses, it may not be directly appropriate for describing all the strategies for grazing of shrubs or for other objectives that may be written into a grazing management plan. In addition to the factors considered by the index, other strategies are not evaluated, such as mixing up the season of use from year to year, dual species grazing to spread the use among a greater variety of plant species, rotation of rest or 3 or more pastures in rest rotation, intense grazing to create or maintain fuel breaks, targeted grazing to address specific weed species, or using animal impact to plant seeds or enhance establishment of perennial seedlings. While none of the index-inspired or other strategies is a cure-all, each could be used in specific settings to accomplish specific treatments or objectives.

Grazing Response Index–inspired strategies

The greatest impact on index scores and plant growth will be achieved through shorter duration of grazing periods during the growing season in a given use area. A use area within a pasture is a significant area grazed differently from other areas within that pasture. A field or pasture can easily be looked at in terms of use areas, as opposed to considering the entire field, pasture or allotment. Short durations of use are especially important during fast plant growth and also result in longer recovery periods for plant growth and regrowth. Strategies for the grazing response index could be worded in a management plan as:

- Graze any one area within the pasture or allotment for only ____ number of days within the growing season.

- Graze for only ____ part or fraction of the growing season in any one year. Dates for this could be specified for greater clarity, but this would reduce flexibility. This would also lead to confusion or detail, depending on the number of different plant communities in the pasture and their differences in growth curve dates and shapes.

- Graze during the dormant season.

- Graze any one area for no more than ____ weeks between March 1 and Oct. 1

- Graze for ____ level of utilization, stubble height, or residual dry matter during the growing season. The level could be adjusted by the season and the plant community, depending of the sensitivity of the plants at that time and their ability to recover in an average year (think triggers and end-point indicators) (Swanson et al. 2018).

- Either graze any one area within the pasture or allotment for only ____ number of days within the growing season, OR move livestock to a new use area whenever (utilization, stubble height or residual dry matter) exceeds ____.

Mixing it up

Animals go to different places in a pasture depending on the season of use. They also eat different plants and plant parts. Plants grow different plant parts or emphasize different physiological processes during different periods of the growing season. So, mixing up the season of use among years in each pasture or use area enables plants to thrive. Strategies for this could be worded in a management plan as:

- Do not graze any one use area at the same time as in the previous year.

- Do not graze any one use area at the same stage in plant growth as in the previous year.

- Plan at least ____ number of calendar days between the grazing dates in sequential years.

- After grazing an area, wait at least 12 to ____ months before grazing it again.

- Specific periods of use for each pasture in a three, four or five-pasture deferred pasture rotation grazing system.

Multiple species of grazers

Dual-species grazing spreads the use among a greater variety of plant species. Most often, cattle in many places graze primarily grasses. However animal preferences are always adjusted depending on what is available, as well as learned behaviors taught by their mothers, peers and experiences. Sheep and goats tend to prefer forbs (wildflowers) and shrubs. With their smaller mouths, they are able to select more nutritious parts of plants. They also have a reputation for use of steep terrain, and they are generally herded in rangeland settings. Herding can greatly modify the location of grazing and grazing distribution. Strategies related to dual-species grazing could be worded in a management plan as:

- Which species are planned for grazing in which areas or seasons.

- The proportion of total animal unit months (AUMs) of forage to be allocated to each livestock species.

Rest and recovery

While rest is evaluated in the grazing response index as a plus four (+4), rotation of rest or rest rotation often appears like an oscillation between positive and negative index scores. To plan a strategy around these rest-centered options, it may help to recognize that a tradeoff has been selected. While rest enables full recovery with adequate moisture, it also may favor cheatgrass, which gets a free ride for a year and may thrive with the extra litter. Rest during a drought provides less recovery. Also, grazing management plans that rely on rest are often stressful in other years due to longer seasons of use among fewer pastures. Strategies for rest and/or recovery could be worded in a management plan as:

- Define a sequence for grazing three, four or five pasture rest rotation grazing system.

- Specify periods of use for each pasture in a three, four or five-pasture rest rotation grazing system.

- Alternate years of grazing with years of no grazing or do not graze for an entire growing season at least one year in ____ years.

- After grazing an area, wait at least 13 to ____ months before grazing it again.

- After grazing an area during the boot stage of perennial grass growth, wait until after an average precipitation year growing season, (or two below average precipitation growing seasons) before grazing it again during the growing season.

Grazing for fuels management

Intense grazing to create or maintain fuel breaks is sometimes prescribed for some areas within a landscape (Davies et al. 2015a; 2015b; 2016; Perryman 2018; Swanson et al. 2018). Since this is the strategy, and fire or mega-fires may be considered a greater risk, usual notions about grazing for plant health may or may not apply. While grazing for a limited level of utilization or even grazing for plant health may not be an issue in areas of annuals that have crossed an ecological threshold, the grazing period may matter a lot in areas with remaining perennial forage plants. It has been said that wet years or high-production years have led to much greater rangeland impacts through fire than impacts caused by grazing in drought years. It has also been observed that there is generally a year or more lag time between the abundant growth in a wet growing season and the period of high fire risk. Strategies for managing fuels across broad rangelands or in specific areas could be worded in a management plan as:

- Graze every pasture every year.

- Graze for spatial variation of fine fuel levels or to break up fuel continuity with some pastures or use areas grazed more intensely.

- After wet productive growing seasons, graze strategically to create fuel breaks in optimum locations

- Graze for at least ____ percent utilization on target species.

- Graze for less than ____ pounds per acre residual dry matter.

- Conduct either of the above before the season of greatest fire danger, say by ____ date.

- Either use at least _____ utilization or leave less than ____ residual dry matter before the next growing season (to reduce residual fine fuels).

- Either use at least ____ utilization or leave less than ____ residual dry matter by grazing after the growing season of wet years and before the next growing season (to reduce residual fine fuels and keep perennials thriving in the years when it matters most).

Targeted grazing

Targeted grazing has become a tool to address specific weed species, especially invasive weeds. This can be accomplished by using the natural forage selectivity of different kinds of livestock, for example sheep or goats eating forbs, and by timing the use period for periods when the targeted species of weed are likely to be relatively more palatable. Ideally, the weeds would be grazed during a time that prevents most seed production or spread of seeds by livestock. Concerns associated with targeted grazing could also be addressed as mechanisms for avoidance of a problem. Strategies for this could be worded in a management plan as:

- Use targeted grazing to reduce the area of (or to prevent the spread of) ____ weed species.

- Spell out the prescription for the targeted grazing.

- Target the grazing period before the time when weed seeds become ripe or when perennial forage plants become most vulnerable, the boot stage.

- Target the grazing period for after weed seeds have dropped and perennial plants have gone dormant.

- See strategies for dual-species grazing above.

Grazing for impact

Animal impact can be used to crush vegetation, cover seeds or trample them into soil with animal fertilizer, or to remove thatch or litter impeding plant growth. Feeding livestock on lands for reclamation can add organic matter and nutrients. These steps can enhance establishment of rangeland seedings, especially on difficult soils that may lack organic matter or nutrients. Strategies for this could be worded in a management plan as:

- After seeding, feed weed-free hay on the seeded area.

- Place salt and/or protein supplement in new locations each year.

- Use stockmanship to develop herd effect by turning the herd over specific areas after seed ripe.

- At least once in three years, graze intensely to remove more than ____ percent of thatch and litter.

Conclusion

The strategies listed above, and others, can be adjusted, mixed and matched to achieve results important to the ranch, rangelands and stakeholders. The value of any strategy depends on the location, including the ecological site or disturbance response group, the state and phase of current vegetation and soils, the management context of relative priorities, opportunities for implementation, and how well they would lead toward SMART resource objectives. SMART objectives are Specific (what is to change or not), Measureable (with standard monitoring methods), Achievable (given the site, state and planned management), Relevant (to the planned management), and Timely or Trackable (reflecting present local and broader scale priorities, and readiness for the desired response). Strategies may change through time as monitoring reveals a need or opportunity or in a planned manner with a sequence of actions or treatments. Monitoring the implementation and success of strategies is essential to understand progress toward objectives and to adapt management when needed.

References

Davies, K. W., J. D. Bates, C. S. Boyd, and T. J. Svejcar. 2016. Prefire Grazing by Cattle Increases Postfire Resistance to Exotic Annual Grass (Bromus tectorum) Invasion and Dominance for Decades. Ecology and Evolution, 6(10):3356– 336.

Davies, K., C. Boyd, J. Bates, and A. Hulet. 2015a. Dormant Season Grazing May Decrease Wildfire Probability by Increasing Fuel Moisture and Reducing Fuel Amount and Continuity. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 24:849- 856. DOI: 10.1071/WF14209.

Davies, K., C. Boyd, J. Bates, and A. Hulet. 2015b. Winter Grazing Can Reduce Wildfire Size, Intensity and Behaviour in a Shrub-grassland. International Journal of Wildland Fire, #854. http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/WF15055.

Perryman, B. L., B. Schultz, K. McAdoo, R. Alverts, J. Cervantes, S. Foster, G. McCuin, and S. Swanson. 2018. Viewpoint: An alternative Management Paradigm for Plant Communities Affected by Invasive Annual Grasses in the Intermountain West. Rangelands, 40(3):77-82.

Perryman, B. L., L. B. Bruce, P. T. Tueller, and S. R. Swanson. 2006. Ranchers’ Monitoring Guide. University of Nevada Cooperative Extension Educational Bulletin EB-06-04. 48 pp. http://www.unce.unr.edu/publications/files/ag/2006/eb0604.pdf (An update of this is in process at the time of publication.) Reed, F., R. Roath, and D. Bradford. 1999. The Grazing Response Index: A Simple and Effective Method to Evaluate Grazing Impacts. Rangelands, August:3-6.

Stringham, T. K., P. Novak-Echenique, D. K. Snyder, S. Peterson, and K. A. Snyder. 2016. Disturbance Response Grouping of Ecological Sites Increases Utility of Ecological Sites and State-and-Transition Models for Landscape Scale Planning in the Great Basin. Rangelands, 38(6):371-378.

Swanson, S. 2016. Integrated Lentic Riparian Grazing Management. International Rangelands Congress X, July 18-22. Saskatoon, SK, Canada. 2 pp.

Swanson, John C., Peter J. Murphy, Sherman R. Swanson, Brad W. Schultz, and J. Kent McAdoo. 2018. Plant Community Factors Correlated with Wyoming Big Sagebrush Site Responses to Fire. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 71(1):67- 76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2017.06.013

Swanson, S., D. Voth, and J. C. Cervantes. 2019 Planning for Plant Growth Using the Grazing Response Index. University of Nevada Cooperative Extension Information Publication 2019-03 5 pp.

Swanson, S., S. Wyman, and C. Evans. 2015. Practical Grazing Management to Maintain or Restore Riparian Functions and Values. Journal of Rangeland Applications, 2:1-28.

Swanson, S., B. Schultz, P. Novak-Echenique, K. Dyer, G. McCuin, J. Linebaugh, B. Perryman, P. Tueller, R. Jenkins, B. Scherrer, T. Vogel, D. Voth, M. Freese, R. Shane, and K. McGowan. 2018. Nevada Rangeland Monitoring Handbook, Third Edition. University of Nevada Cooperative Extension Special Publication SP-18-03. 122 pp. http://www.unce.unr.edu/publications/sp_2018_03.aspx

Teague, Richard, Fred Provenza, Urs Kreuter, Tim Steffens and Matt Barnes. 2013. Multi-paddock grazing on rangelands: Why the perceptual dichotomy between research results and rancher experience? Journal of Environmental Management 128:699-717.

Wyman S., D. Bailey, M. Borman, S. Cote, J. Eisner, W. Elmore, B. Leinard, S. Leonard, F. Reed, S. Swanson, L. Van Riper, T. Westfall, R. Wiley, and A. Winward. 2006. Riparian Area Management -- Management Processes and Strategies for Grazing Riparian-Wetland Areas. U. S. Bureau of Land Management. Technical Reference TR 1737-20. 119 pp. http://naes.unr.edu/swanson/Extension/PFCTeam.aspx

This publication was supported by Western Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (Western SARE).